يوِري موسڤني

|

يوِري كاگوتا موسڤني Yoweri Kaguta Museveni | |

|---|---|

| رئيس أوغندا | |

| الحالي | |

|

تولى المنصب 25 يناير 1986 34 سنة, 133 يوم | |

| رئيس الوزراء |

Samson Kisekka George Cosmas Adyebo Kintu Musoke Apolo Nsibambi |

| نائب الرئيس |

Samson Kisekka Specioza Kazibwe Gilbert Bukenya |

| سبقه | تيتواوكلو |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | ح. 1944 (العمر 75–76) نتونگامو، محمية أوغندا |

| الحزب | حركة المقاومة الوطنية (NRM) |

| الزوج | جانت موسڤني |

| الدين | Born-again Christian |

يوِري كاگوتا موسڤني (◄ انصت (مساعدة·معلومات)) Yoweri Kaguta Museveni (و. 1944،نتونگامو، محمية اوغندا) هورئيس اوغندا منذ 29 يناير 1986.

الحياة المبكرة (1944–1972)

ولد في عام1944 في مقاطعة مبارارا نتونگامو, محمية أوغندا وتخرج في مدرسة نتارا، مبارا (1961- 66)؛ حصل على بكالوريوس العلوم السياسية والاقتصاد والقانون، جامعة دار السلام، تنزانيا (1967- 70).

تاريخه السياسي

عمل بجبهة تحرير موزمبيق وهوطالب جامعي؛ مساعد باحث بمخط الرئيس (1971)؛ نُفي إلى تنزانيا وشارك في العمليات العسكرية ضد عيدي أمين؛ مؤسس جبهة الانقاذ الوطني(1972) التي أسقطت عيدي أمين عام (1979)؛ وزير الدولة، ثم وزير الدفاع(1979)؛ وزير التعاون الإقليمي (1979- 80)؛ نائب رئيس اللجنة العسكرية؛ رئيس حركة أوغندا الوطنية (1980)؛ مؤسس حركة المقاومة الوطنية وجيش المقاومة الوطني (1981)؛ زعيم المقاومة الحربية ضد ميلتون أوبوتي (1981- 86)؛ نائب الرئيس (ديسمبر 1985)؛ رئيس حركة المقاومة الوطنية (حالياً)؛ رئيس القيادة العليا والقائد الأعلى لجيش المقاومة الوطني (حالياً)؛ رئيس الجمهورية ووزير الدفاع من 26/1/1986- إلى الآن)؛ رئيس منطقة التجارة التمييزية (1987- 88)؛ رئيس منظمة الوحدة الأفريقية (1992-93)، وهومن أبرز العاملين علي إنشاء إمبراطورية التوتسي للهيمنة علي وسط أفريقيا بمساندة الولايات المتحدة الأمريكية وإسرائيل.

الحرب في الأدغال (1981–86)

حكم اوبوته العائد وجيش المقاومة الوطني

| اوغندا |

|

هذه الموضوعة هي جزء من سلسلة: |

|

|

|

|

دول أخرى • أطلس بوابة السياسة |

Museveni returned with his supporters to their rural strongholds in the Bantu-dominated south and southwest to form the Popular Resistance Army (PRA). There they planned a rebellion against the second Obote regime, popularly known as "Obote II", and its armed forces, the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). The insurgency began with an attack on an army installation in the central Mubende district onستة February 1981. The PRA later merged with former president Yusufu Lule's fighting group, the Uganda Freedom Fighters (UFF), to create the National Resistance Army (NRA) with its political wing, the National Resistance Movement (NRM). Two other rebel groups, the Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) and Former Uganda National Army (FUNA), formed in West Nile from the remnants of Amin's supporters, engaged Obote's forces.

The NRM/A developed a "Ten-point Programme" for an eventual government, covering democracy, security, consolidation of national unity, defending national independence, building an independent, integrated and self-sustaining economy, improvement of social services, elimination of corruption and misuse of power, redressing inequality, cooperation with other African countries and a mixed economy.

By July 1985, Amnesty International estimated that the Obote regime had been responsible for more than 300,000 civilian deaths across Uganda, although the CIA World Factbook puts the number at over 100,000. The human rights organisation had made several representations to the government to improve its appalling human rights record from 1982. Abuses were particularly conspicuous in an area of central Uganda known as the Luweero Triangle. Reports from Uganda during this period brought international criticism to the Obote regime and increased support abroad for Museveni's rebel force. Within Uganda, the brutal suppression of the insurgency aligned the Buganda, the most numerous of Uganda's ethnic groups, with the NRA against the UNLA, which was seen as being dominated by northerners, especially the Lango and Acholi. Until his death in 2005, Milton Obote blamed the Luwero abuses on the NRA.

اتفاقية نيروبي 1985

On 27 July 1985, subfactionalism within the UPC government led to a successful military coup against Obote by his former army commander, Lieutenant-General Tito Okello, an Acholi. Museveni and the NRM/A were angry that the revolution for which they had fought for four years had been "hijacked" by the UNLA, which they viewed as having been discredited by gross human rights violations during Obote II. Despite these reservations, however, the NRM/A eventually agreed to peace talks presided over by a Kenyan delegation headed by President Daniel arap Moi.

The talks, which lasted from 26 August to 17 December, were notoriously acrimonious and the resultant ceasefire broke down almost immediately. The final agreement, signed in Nairobi, called for a ceasefire, demilitarisation of Kampala, integration of the NRA and government forces, and absorption of the NRA leadership into the Military Council. These conditions were never met.

The prospects of a lasting agreement were limited by several factors, including the Kenyan team's lack of an in-depth knowledge of the situation in Uganda and the exclusion of relevant Ugandan and international actors from the talks, inter alia. In the end, Museveni and his allies refused to share power with generals they did not respect, not least while the NRA had the capacity to achieve an outright military victory.

التقدم نحوكمپالا

While supposedly involved in the peace negotiations, Museveni had courted General Mobutu of Zaire in an attempt to forestall the involvement of Zairean forces in support of Okello's military junta. On 20 January 1986, however, several hundred troops loyal to Idi Amin were accompanied into Ugandan territory by the Zairean military. The forces intervened in the civil conflict following secret training in Zaire and an appeal from Okello ten days previously. Mobutu's support for Okello was a score Museveni would settle years later, ordering Ugandan forces into the conflict which would finally topple the Zairean leader.

By this stage, however, the NRA had developed an unstoppable momentum. By 22 January, government troops in Kampala had begun to quit their posts en masse as the rebels gained ground from the south and south-west. On the 25th, the Museveni-led faction finally overran the capital. The NRA toppled Okello's government and declared victory the next day.

Museveni was sworn in as president three days later on 29 January. "This is not a mere change of guard, it is a fundamental change," said Museveni after a ceremony conducted by British-born chief justice Peter Allen. Speaking to crowds of thousands outside the Ugandan parliament, the new president promised a return to democracy and said: "The people of Africa, the people of Uganda, are entitled to a democratic government. It is not a favour from any regime. The sovereign people must be the public, not the government."

صعوده إلى السلطة (1986–96)

التجديدات الاقتصادية والسياسية

The post-Amin regimes in Uganda were characterised by corruption, factionalism and an inability to restore order and acquire popular legitimacy. Museveni needed to avoid repeating these mistakes if his new government was not to befall the same fate. The NRM declared a four-year interim government, composing a broader ethnic base than its predecessors. The representatives of the various factions were nevertheless hand-picked by Museveni. The sectarian violence which had overshadowed Uganda's recent history was put forward as a justification for restricting the activities of the political parties and their ethnically distinct supporter bases. The non-party system did not prohibit political parties, but prevented them from fielding candidates directly in elections. The so-called "Movement" system, which Museveni said claimed the loyalty of every Ugandan, would be a cornerstone in politics for nearly twenty years.

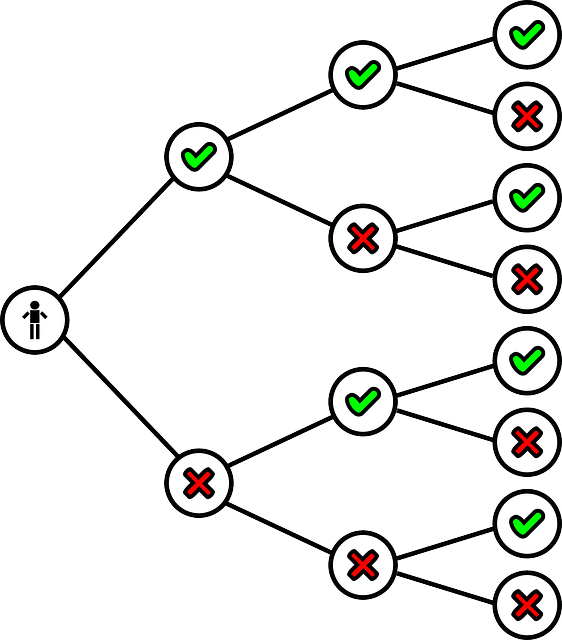

A system of Resistance Councils, directly elected at the parish level, was established to manage local affairs, including the equitable distribution of fixed-price commodities. The election of Resistance Councils representatives was the first direct experience many Ugandans had with democracy after many decades of varying levels of authoritarianism, and the replication of the structure up to the district level has been credited with helping even people at the local level understand the higher-level political structures.

The new government enjoyed widespread international support, and the economy that had been damaged by the civil war began to recover as Museveni initiated economic policies designed to combat key problems such as hyperinflation and the balance of payments. Abandoning his Marxist ideals, Museveni embraced the neoliberal structural adjustments advocated by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Uganda began participating in an IMF Economic Recovery Program (ERP) in 1987. Its objectives included the restoration of incentives in order to encourage growth, investment, employment and exports; the promotion and diversification of trade with particular emphasis on export promotion; the removal of bureaucratic constraints and divestment from ailing public enterprises so as to enhance sustainable economic growth and development through the private sector; the liberalisation of trade at all levels.

الصراع والعلاقات الاقليمية

After January 1986, Museveni continued in his role as Commander-in-Chief of the NRA. The Kenyan government of Daniel arap Moi was initially suspicious of the new NRM government's alleged support for Kenyan dissident groups. Tensions culminated in a non-violent military standoff at Busia on the Kenya-Uganda border in late 1987. Any closure of borders with Kenya would have been extremely damaging to landlocked Uganda's economy, whose access to the Indian Ocean via the port at Mombasa depends upon Kenya.

During their guerrilla war against the government of Milton Obote, the National Resistance Army recruited anyone who was willing to fight, regardless of nationality. Persecution at the hands of the Obote regime encouraged many Rwandan exiles living in Uganda to join the ranks of the NRA. Several years into the Museveni government, the Ugandan army still had several thousand Rwandans on its payroll. On the night of 30 September 1990, 4,000 Rwandan members of the NRA left their barracks in secrecy, joining other forces to invade Rwanda from Ugandan territory. It transpired that the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF) was operating a large membership within the NRA using a clandestine cell structure.

The RPF was a movement of Rwandan exiles opposed to the government of Juvénal Habyarimana who were linked to Museveni and the NRM. It must be remembered that Museveni was also trying gain roots to his ancestors in Rwanda. Being a Tutsi himself he played a key role in ensuring that his brothers and sisters find solace at home.RPF leaders included Fred Rwigema and Paul Kagame, both Rwandan exiles and founder members of the NRM. During the initial stages of the invasion, Museveni and Habyarimana were both attending a UN summit in the United States. It has been claimed that the date for the RPF mobilisation was set to allow Museveni to distance himself from their actions until it was too late to stop them. The Rwandan army managed to expel the invasion only after extensive reinforcement from Belgium, France and Zaire.

Museveni was blamed for complicity in the September 1990 invasion and/or not having control of his army. The RPF melted away into the Virunga Mountains straddling the Rwanda-Uganda border. The Habyarimana government accused Uganda of allowing the RPF to use its territory as a rear base, responding by shelling Ugandan villages on the border. Uganda is widely believed to have returned fire, which would probably have protected RPF positions.[] These exchanges forced more than 60,000 from their homes. Despite the negotiation of a security pact, in which both countries agreed to cooperate in maintaining security along their common border, a resurgent RPF had occupied much of the northern territory of Rwanda by 1992.

In April 1994, a plane carrying President Habyarimana of Rwanda and President Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi was shot down over Kigali airport. This precipitated the Rwandan genocide in which an estimated 800,000 people perished. The Rwandan Patriotic Front overran Kigali and took power with the help of the Ugandan army.

In April 1995, Uganda cut off diplomatic relations with Sudan in protest at Khartoum's support for the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), a rebel group active in northern Uganda. Sudan, in turn, claimed that Uganda was providing support to the Sudan People's Liberation Army. Both groups were suspected of operating across the porous Uganda-Sudan border. Disputes between Uganda and Sudan date back to at least 1988. Ugandan refugees sought shelter in southern Sudan during the Amin and Obote II regimes. After the NRM had come to power in 1986, however, many of these refugees joined the Ugandan rebel groups including the West Nile Bank Front and later the LRA. For a significant period, the Museveni government viewed Sudan as the most significant threat to Ugandan security.

حقوق الإنسان والأمن الداخلي

The NRM came to power promising to restore security and respect for human rights. Indeed, this was part of the NRM's ten-point programme, as Museveni noted in his swearing in speech:

| ” | The second point on our programme is security of person and property. Every person in Uganda must [have absolute] security to live wherever he wants. Any individual, any group who threatens the security of our people must be smashed without mercy. The people of Uganda should die only from natural causes which are beyond our control, but not from fellow human beings who continue to walk the length and breadth of our land. | “ |

Although Museveni now headed up a new government in Kampala, the NRM could not project its influence fully across Ugandan territory, finding itself fighting a number of insurgencies. From the beginning of Museveni's presidency, he drew strong support from the Bantu-speaking south and southwest, where Museveni had his base. Museveni managed to get the Karamojong, a group of semi-nomads in the sparsely populated north-east that had never had a significant political voice, to align with him by offering them a stake in the new government. However, the northern region along the Sudanese border proved more troublesome. In the West Nile sub-region, inhabited by Kakwa and Lugbara (who had previously supported Amin), the UNRF and FUNA rebel groups fought for years until a combination of military offensives and diplomacy pacified the region; the leader of the UNRF, Moses Ali, gave up his struggle to become Second Deputy Prime Minister. People from the northern parts of the country viewed the rise of a government led by a person from the south with great trepidation. Rebel groups sprang up among the Lango, Acholi and Teso, though they were overwhelmed by the strength of the NRA except in the far north where the Sudanese border provided a safe haven. The Acholi rebel Uganda People's Democratic Army (UPDA) failed to dislodge the NRA occupation of Acholiland, leading to the desperate chiliasm of the Holy Spirit Movement (HSM). The defeat of both the UPDA and HSM left the rebellion to a group that eventually became known as the Lord's Resistance Army, which would turn upon the Acholi themselves.

The NRA subsequently earned a reputation for respecting the rights of civilians, – although Museveni later received criticism for using child soldiers. Undisciplined elements within the NRA's soon tarnished a hard-won reputation for fairness. "When Museveni's men first came they acted very well – we welcomed them," said one villager, "but then they started to arrest people and kill them."

In March 1989, Amnesty International published a human rights report on Uganda, entitled Uganda, the Human Rights Record 1986–1989. It documented gross human rights violations committed by NRA troops. In one of the most intense phases of the war, between October and December 1988, the NRA forcibly cleared approximately 100,000 people from their homes in and around Gulu town. Soldiers committed hundreds of extrajudicial executions as they forcibly moved people, burning down homes and granaries. However, there were few reports of the systematic torture, equivalent to those committed during Amin and Obote's regimes. In its conclusion, the report offered some hope:

| ” | Any assessment of the NRM government's human rights performance is, perhaps inevitably, less favourable after four years in power than it was in the early months. However, it is not true to say, as some critics and outside observers, that there has been a continuous slide back towards gross human rights abuse, that in some sense Uganda is fated to suffer at the hands of bad government. | “ |

إنتداب ديموقراطي حديث (1996–2001)

الانتخابات

The first Elections under Museveni's governance were held onتسعة May 1996. Museveni defeated Paul Ssemogerere of the Democratic Party, who contested the election as a candidate for the "Inter-party forces coalition", and the upstart candidate, Mohamed Mayanja. Museveni won with a landslide 75.5 per cent of the vote from a turnout of 72.6 per cent of eligible voters. Although international and domestic observers described the vote as valid, both the losing candidates rejected the results. Museveni was sworn in as president for the second time on 12 May 1996.

The main weapon in Museveni's campaign was the restoration of security and economic normality to much of the country. A memorable electoral image produced by his team depicted a pile of skulls in the Luwero Triangle. This powerful symbolism was not lost on the inhabitants of this region, who had suffered rampant insecurity during the civil war. The other candidates had difficulty matching Museveni's efficacy in communicating his key message. Museveni seemed to have a remarkable ability to relate political messages by using grass-roots language, especially with people from the south. The metaphor of "carrying a grindstone for leadership", referring to an "authoritative individual, bearing the burden of authority", was just one of many imaginative images he created for his campaign. He would often deliver these in the appropriate local colloquial language, demonstrating respect and attempting to transcend tribalistic politics. Museveni's fluency in الإنگليزية, Luganda, Runyankole and Swahili often helped him forward his message.

Until the prospect of presidential elections, Ssemogerere (Museveni's concurrent political rival) had been a minister in the NRM government. His decision to challenge the record of Museveni and the NRM, rather than claim a stake in Museveni's "movement", was seen as naive opportunism, and regarded as a political error. Ssemogerere's alliance with the UPC was anathema to the Baganda, who might otherwise have lent him some support as the leader of the Democratic Party. Ssemogerere also accused Museveni of being a Rwandan, a statement often repeated by Museveni's opponents because of his birthplace near the Uganda-Rwanda border, and his supposedly Rwandan origins (Museveni is an ethnic Munyankole, kin to the Banyarwanda of Rwanda), and his army of being dominated by Rwandans, which included current Rwandan president Paul Kagame.

The second set of elections were held in 2001. President Museveni beat his rival Kizza Besigye as he sailed through with 69% of the vote. Dr Besigye had been a close confidant of the president and he was his bush war physician. They however had a fallout shortly before the 2001 elections, when Dr Besigye decided to stand for presidency. The 2001 election campaigns were a heated affair with president Museveni threatening his rival to put him "six feet under".

The election culminated into a petition filed by Dr Besigye at the Supreme Court of Uganda. The court ruled that the elections were not free and fair but declined to nullify the outcome by a 3:2 majority decision. It was held that the many cases of election malpractice did not however affect the result in a substantial manner. Justices Benjamin Odoki (Chief justice), Alfrerd Karokora, and Joseph Mulenga ruled in favor of the respondents while Justices Aurthur Haggai Oder (RIP) and John Tsekoko ruled in favor of Dr Besigye.

The most recent presidential elections were held in 2006 where again Museveni prevailed over Dr Besigye scoring 59% of the vote. The election petition in this case had more evidence of election malpractice but by a 4:3 decision, the result was upheld. As before, the judges ruled as they ruled in the 2001 petition. The additional two judges were Justice George W. Kanyeihamba ruling in favor of Dr Besigye and Justice Bart Katureebe in favor of President Museveni and the electoral commission. Dr Besigye predicted that that could be the last presidential election petition filed in the then constituted Supreme court.

الاعتراف الدولي

Museveni has won praise from Western governments for his adherence to IMF Structural adjustment programs, i.e. privatising state enterprises, cutting government spending and urging African self-reliance. Museveni was elected chairperson of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in 1991 and 1992. He permitted a free atmosphere within which the news media could operate, and private FM radio stations flourished during the late 1990s. Perhaps Museveni's most widely noted accomplishment has been his government's successful campaign against AIDS. During the 1980s, Uganda had one of the highest rates of HIV infection in the world, but now Uganda's rates are comparatively low, and the country stands as a rare success story in the global battle against the virus (see AIDS in Africa). One of the campaigns headed by Museveni to fight against AIDS was the ABC program. The ABC program had three main parts "Abstain, Be faithful, or use Condoms if A and B are not practiced. In April 1998, Uganda became the first country to be declared eligible for debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, receiving some US$700 million in aid. Museveni was lauded for his affirmative action program for women in the country, he was served by a female vice-president, Specioza Kazibwe, for nearly a decade, and has done much to encourage women to go to college. On the other hand, Museveni has resisted calls for greater women's family land rights (the right of women to own a share of their matrimonial homes).

From the mid-1990s, Museveni was seen to exemplify a new breed of African leadership, the antithesis of the "big men" who had dominated politics in the continent since independence. This section from a New York Times article in 1997 is illustrative of the high esteem in which Museveni was held by the western media, governments and academics:

- These are heady days for the former guerilla who runs Uganda. He moves with the measured gait and sure gestures of a leader secure in his power and his vision. It is little wonder. To hear some of the diplomats and African experts tell it, President Yoweri K. Museveni started an ideological movement that is reshaping much of Africa, spelling the end of the corrupt, strong-man governments that characterized the cold-war era. These days, political pundits across the continent are calling Mr. Museveni an African Bismarck. Some people now refer to him as Africa's "other statesman," second only to the venerated South African President, Nelson Mandela.

In official briefing papers from Madeleine Albright's December 1997 Africa tour as Secretary of State, Museveni was called a "beacon of hope" who runs a "uni-party democracy," despite Uganda not permitting multiparty politics.

These generous statements have since been re-evaluated.

الصراع الاقليمي

In Uganda, there were significant numbers of ethnic Rwandan Tutsi immigrants – who comprised a significant numbers of NRA fighters. The Uganda-based Tutsi-dominated Rwandese Patriotic Front rebel group were close allies of the NRA, and once Museveni had solidified his hold on central power, he lent his support to their cause. Unsuccessful attacks were launched by the RPF against the Hutu government of Rwanda in the first half of the 1990s from bases in southwest Uganda. It was not until the Rwandan Genocide of 1994 that the RPF took power and its head, Paul Kagame (a former soldier in Museveni's army), became president.

Following the Rwandan Genocide, the new Rwandan government felt threatened by the presence (across the Rwandan border in Congo - known then as Zaïre) of former Rwandan soldiers and members of the previous regime. These soldiers were aided by Mobutu Sese Seko – leading Rwanda (with the aid of Museveni) and Laurent Kabila's rebels to overthrow him and take power in Congo. (see main article: First Congo War).

In August 1998, Rwanda and Uganda undertook to invade Congo again, this time to overthrow Museveni and Kagame's former ally - Kabila (see main article: Second Congo War). Museveni and a few close military advisers alone made the decision to send the UPDF into Congo. A number of highly placed sources indicate that the Ugandan parliament and civilian advisers were not consulted over the matter, as is required by the 1995 constitution. Museveni apparently persuaded an initially reluctant High Command to go along with the venture. "We felt that the Rwandese started the war and it was their duty to go ahead and finish the job, but our President took time and convinced us that we had a stake in what is going on in Congo", one senior officer is reported as saying. The official reasons Uganda gave for the intervention were to stop a "genocide" against the Banyamulenge in DRC in concert with Rwandan forces, and that Kabila had failed to provide security along the border and was allowing the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) to attack Uganda from rear bases in DRC. In reality, the UPDF were not deployed in the border region but more than 1,000 kilometres (over 600 miles) to the west of Uganda's frontier with Congo and in support of the Mouvement de Libération du Congo (MLC) rebels seeking to overthrow Kabila. As such, they were unable to prevent the ADF from invading the major town of Fort Portal and taking over a prison in Western Uganda.

Troops from Rwanda and Uganda plundered the country's rich mineral deposits and timber. The United States responded to the invasion by suspending all military aid to Uganda, a disappointment to the Clinton administration, which had hoped to make Uganda the centrepiece of the African Crisis Response Initiative. In 2000, Rwandan and Ugandan troops exchanged fire on three occasions in the Congolese city of Kisangani, leading to tensions and a deterioration in relations between Kagame and Museveni. The Ugandan government has also been criticised for aggravating the Ituri conflict, a sub-conflict of the Second Congo War. In December 2005, the International Court of Justice ruled that Uganda must pay compensation to the Democratic Republic of the Congo for human rights violations during the Second Congo War.

In the north, Uganda had supported Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) in the Second Sudanese Civil War against the government in Khartoum even before Museveni's rise. The continued support for the SPLA, led by Museveni's old acquaintance John Garang, led Sudan to support the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) and other anti-Museveni rebel groups in the mid-1990s. The resulting insecurity and conflicts have caused widespread human displacement, death and destruction in southern Sudan and northern Uganda. Subsequent warming of relations with Sudan led to a pledge to stop supporting hostile proxy forces (from both sides) and the granting of approval to the UPDF to attack the LRA within Sudan itself.

الفترة الثانية (2001–2006)

انتخابات 2001

In 2001 Museveni won the presidential elections by a substantial majority, with his former friend and personal physician Kizza Besigye as the only real challenger. In a populist publicity stunt, a pentagenarian Museveni travelled on a bodaboda motorcycle taxi to submit his nomination form for the election. Bodaboda is a cheap and somewhat dangerous (by western standards) method of transporting passengers around towns and villages in East Africa.

There was much recrimination and bitterness during the 2001 presidential elections campaign, and incidents of violence occurred following the announcement of the results – which were won by Museveni. Besigye challenged the election results in the Supreme Court of Uganda. Two of the five judges concluded that there were such illegalities in the elections, and that the results should be rejected. The other three judges decided that the illegalities did not affect the result of the election in a substantial manner, but stated that "there was evidence that in a significant number of polling stations there was cheating" and that in some areas of the country, "the principle of free and fair election was compromised." Besigye was briefly detained and questioned by the police, allegedly in connection with the offense of treason. In September he fled to the USA claiming his life was in danger.

التعددية السياسية والتغيير الدستوري

After the elections, political forces allied to Museveni began a campaign to slacken constitutional limits on the presidential term to allow him to stand for election again in 2006. The 1995 Uganda's constitution provided for a two-term limit on the tenure of the president. Given Uganda's history of dictatorial regimes, this check-and-balance was designed to prevent a dangerous centralisation of power around a long-serving leader. This period witnessed the removal of key and influential Museveni supporters from his administration, including his childhood friend Eriya Kategaya and cabinet minister Jaberi Bidandi Ssali.

Moves to alter the constitution, and alleged attempts to suppress opposition political forces have attracted criticism from domestic commentators, the international community and Uganda's aid donors. In a press release, the main opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), accused Museveni of engaging in a "life presidency project", and for bribing members of parliament to vote against constitutional amendments, FDC leaders claimed:

- The country is polarized with many Ugandans objecting to [the constitutional amendments]. If Parliament goes ahead and removes term limits this may cause serious unrest, political strife and may lead to turmoil both through the transition period and there after ... We would therefore like to appeal to President Museveni to respect himself, the people who elected him and the Constitution under which he was voted President in 2001 when he promised the country and the world at large to hand over power peacefully and in an orderly manner at the end of his second and last term. Otherwise his insistence to stand again will expose him as a consummate liar and the biggest political fraudster this country has ever known.

As observed by some political commentators, including Wafula Oguttu, Museveni had previously stated that he considered the idea of clinging to office for "15 or more" years ill-advised. Comments by the Irish anti-poverty campaigner Bob Geldof sparked a protest by Museveni supporters outside the British High Commission in Kampala. "Get a grip Museveni. Your time is up, go away," said the former rock star in March 2005, explaining that moves to change the constitution were compromising Museveni's record against fighting poverty and HIV/AIDS. In an opinion article in the Boston Globe and in a speech delivered at the Wilson Center, former U.S. Ambassador to Uganda Johnnie Carson heaped more criticism on Museveni. Despite recognising the president as a "genuine reformer" whose "leadership [has] led to stability and growth", Carson also said, "we may be looking at another Mugabe and Zimbabwe in the making". "Many observers see Museveni's efforts to amend the constitution as a re-run of a common problem that afflicts many African leaders – an unwillingness to follow constitutional norms and give up power".

In July 2005, Norway became the third European country in as many months to announce symbolic cutbacks in foreign aid to Uganda in response to political leadership in the country. The UK and Ireland made similar moves in May. "Our foreign ministry wanted to highlight two issues: the changing of the constitution to lift term limits, and problems with opening the political space, human rights and corruption", said Norwegian Ambassador Tore Gjos. Of particular significance was the arrest of two opposition MPs from the Forum for Democratic Change. Human rights campaigners charged that the arrests were politically motivated. Human Rights Watch stated that "the arrest of these opposition MPs smacks of political opportunism". A confidential World Bank report leaked in May suggested that the international lender might cut its support to non-humanitarian programmes in the Uganda. "We regret that we cannot be more positive about the present political situation in Uganda, especially given the country's admirable record through the late 1990s", said the paper. "The Government has largely failed to integrate the country's diverse peoples into a single political process that is viable over the long term...Perhaps most significant, the political trend-lines, as a result of the President's apparent determination to press for a third term, point downward."

Museveni responded to the mounting international pressure by accusing donors of interfering with domestic politics and using aid to manipulate poor countries. "Let the partners give advice and leave it to the country to decide ... [developed] countries must get out of the habit of trying to use aid to dictate the management of our countries." "The problem with those people is not the third term or fighting corruption or multipartism," added Museveni at a meeting with other African leaders, "the problem is that they want to keep us there without growing.".

In July 2005, a constitutional referendum lifted a 19-year restriction on the activities of political parties. In the non-party "Movement system" (so called "the movement") instituted by Museveni in 1986, parties continued to exist, but candidates were required to stand for election as individuals rather than representative of any political grouping. This measure was ostensibly designed to reduce ethnic divisions, although many observers have subsequently claimed that the system had become nothing more than a restriction on opposition activity. Prior to the vote, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) spokesperson stated "Key sectors of the economy are headed by people from the president's home area... We have got the most sectarian regime in the history of the country in spite the fact that there are no parties." Many Ugandans saw Museveni's conversion to political pluralism as a concession to donors – aimed at softening the blow when he announces he wants to stay on for a third term. Opposition MP Omara Atubo has said Museveni's desire for change was merely "a facade behind which he is trying to hide ambitions to rule for life".

مقتل حليف أم غريم؟

في 30 يوليو2005، اغتال نائب رئيس الوزراء السوداني جون قرنق عندما تحطمت مرحية الرئيس الاوغندي التي يقلها قرنق عند عودته من محادثات سودانية عقدت في اوغندا. وسبب الحادث حرجا كبيرا للحكومة الاوغندية وللرئيس موسيفيني - حيث كان قربق حليفا سياسيا منذ حتى كانوا زملاء في جامعة دار السلام. وكان قرنق قد عين نائبا لرئيس السودان قبل مقتله بأسابيع قليلة، مما أطاح بأمنيات قيام تحالف اقليمي بين اوغندا وجنوب السودان.

وكثرت التكهنات حول سبب تحطم الطائرة، مما نادى موسيفيني، الى التهديد بإغلاق وسائل الاعلام التي روجت "لنظرية المؤامرة" في مقتل قرنق. في بيان له، أعرب موسفني حتى مثل هذه التكهنات قد تهدد بالأمن القومي. "لن أتسامح مع هذه الصحف الجشعة. لن أتسامح مع أي أي صحيفة تعبث بالأمن القومي - وسوف أغلقها." في اليوم التالي، سحبت رخصة محطة الاذاعة الشعبية لنشر برنامج حول وفاة قرنق. وتم القبض على مذيع الاذاعة أندرومويندا لتعليقاته التي أذاعها في برنامج المحطة حول مقتل قرنق.

انتخابات فبراير 2006

On 17 November 2005, Museveni was chosen as NRMs presidential candidate for the February 2006 elections. His candidacy for a further third term sparked criticism, as he had promised in 2001 that he was contesting for the last term. The arrest of the main opposition leader Kizza Besigye on 14 November – charged with treason, concealment of treason and rape – sparked demonstrations and riots in Kampala and other towns. Museveni's bid for a third term, the arrest of Besigye, and the besiegement of the High Court during a hearing of Besigye's case (by a heavily armed Military Intelligence (CMI) group dubbed by the press as "Black Mambas Urban Hit Squad"), led Sweden, هولندا and the United Kingdom to withhold economic support to Museveni's government due to concerns about the country's democratic development. On 2 January 2006 Besigye was released after the High Court ordered his immediate release.

The 23 February 2006 elections were Uganda's first multi-party elections in 25 years, and was seen as a test of its democratic credentials. Although Museveni did less well than in the previous election, he was elected for another five-year tenure, having won 59% of the vote against Besigye's 37%. Besigye, who alleged fraud, rejected the result. The Supreme Court of Uganda later ruled that the election was marred by intimidation, violence, voter disenfranchisement, and other irregularities. However, the Court voted 4-3 to uphold the results of the election.

الفترة الثالثة (2006-2011)

في عام 2007، اشهجرت قوات موسيفيني مع عملية حفظ السلام للاتحاد الأفريقي في الصومال. وبسبب الحرب بالوكالة في الصومال والتي خاضتها إثيوبيا وإرتريا، فقد أثار هذا التحرك رد عمل عدائي من جانب الحكومة الإرترية.

وثمة مسألة هامة أخرى في الفترة الثالثة لحكم موسيفني، هوقراره بفتح غابة مابرا لزراعة قصب السكر. بينما يدعي موسيفيني حتى هذه الزراعات الجديدة تعتبر من الموارد الهامة لتنمية الاقتصاد الاوغندي، فقد حذر نشطاء البيئة عن ما يمكن حتى ينتج من هذا من أضرار على المنظومة البيئية والتنوع البيولوجي. وأدت هذه التصريحات عن قيام أعمال شغب في 2007 راح ضحيتها شخصين.

أعمال الشغب في سبتمبر 2009

في سبتمبر 2009 رفض موسفيني التصريح لكباكا مويندا موتبي، ملك بگاندا، لزيارة بعض الأماكن في كمپالا. حدثت أعمال شغب أسفرت عن مقتلا 40 شخص.

أصولية مسيحية

قس 2009، أفادت الكثير من المصادر الإخبارية بأن تحقيقات جف شارلت الخاصة حول علاقة موسيفني The Fellowship] المنظمة الأصولية المسيحية الأمريكية (وتعهد أيضا باسم "العائلة"). صرح شارلت حتى دوگلاس كوه، زعيم المنظمة، عهد موسيفيني بأنه "الرجل الرئيسي في أفريقيا". Further international scrutiny accompanied the 2009 Ugandan efforts to institute the death penalty for homosexuality, مع قادة من كندا، المملكة المتحدة، الولايات المتحدة، وفرنسا أعربت عن قلقها بشأن حقوق الإنسان في اوغندا. ونشرت للگارديان (البريطانية) تقريرا عن حتى الرئيس موسيفيني "أظهر تأييده" للمساعي التشريعية، حول موضوعات أخرى، تدعي "أن المثليون الاوروبيون يجندون في أفريقيا"، ونطق حتى العلاقات المثلية ضد مشيئة الرب. وفي 2009 ظهرت الكثير من المحاولات لتشديد العقوبات على المثليين والقوانين المجرمة للمثلية الجنسية.

اهداؤه توراة إلى أحمدينژاد

نطقت صحيفة «معاريڤ» إذا الرئيس الأوغندي، يوري موسفيني، فاجأ المسؤولين الإسرائيليين في زيارته لتل أبيب في 14 نوفمبر 2011، عندما حكى لهم عن الهدية التي أهداها للرئيس الإيراني، محمود أحمدينژاد، في لقائهما الأخير.

وأشارت الصحيفة إلى حتى «موسفيني» أهدى لـ«نجاد» نسخة من التوراة ونطق للرئيس «المذهول» (نجاد)، بحسب وصف «معاريف»: «أمنحك هدية كي تعهد عن الشعب اليهودي وتاريخ الشعب اليهودي»، ولفتت الصحيفة إلى حتى الرئيس الأوغندي نطق للمسؤولين الإسرائيليين عن هذا الموقف: «كان من المهم بالنسبة لي إيصال رسالة مفادها حتى لشعب إسرائيل حقًا تاريخيًا في هذه الأرض».

ونطقت «معاريف»: «إن المسؤولين الإسرائيليين، ومن بينهم رئيس الوزراء، بنيامين نتنياهو، ومسؤولووزارة الخارجية، فوجئوا بأن رئيس أوغندا محب للصهيونية، ويؤمن ويعترف بقصص العهد القديم وبالتاريخ القديم للشعب اليهودي».

الحياة الشخصية

متزوج متزوج وله أربعة أبناء.

أخوه غير الشقيق، الجنرال سالم صالح، كان رئيس أركان الجيش. وقد استنطق ليعمل مع مايكل برنس مؤسس شركة بلاكواتر للمرتزقة. وقد زود برنس سالم صالح برأس مال لتأسيس شركة سراسين للخدمات المشهرة في جنوب أفريقيا والتي تقوم بتقديم خدمات أمنية للحكومة الانتنطقية في الصومال. وتروج أخبار كثيرة عن تورط سالم صالح في تهريب الألماس والمعادن الثمينة من جمهورية الكونغوالديمقراطية.

نقد

ينما يعتبر المعارضون حتى أسلوب موسيفيني في الحكم أصبح استبدادياً علي نحومتزايد، وكان قادة أوربيون قد عرضوا علي موسيفيني هجر الرئاسة قبيل الانتخابات الرئاسية السابقة في أوغندا 2005 لقاء تولي مناصب دولية، ما رفضه الرجل قائلا: بالنسبة لي فإن العمل في الأمم المتحدة سيكون إهانة، لا يمكن حتى أعمل لحساب الأمم المتحدة، في حين حتى أفريقيا ضعيفة، إنني أبحث عن قضية وليس عن وظيفة».

التوريث

ثارت المعارضة الاوغندية ضد الرئيس موسيفيني بعدما قامت بتعيينه قائدا لوحدة الحرس الرئاسية، مما اعتبرته المعارضة اعدادا من الرئيس الأب لننجله النقيب كاينروجابا موهوزي لوراثة الرئاسة. ونطق المتحدث باسم المعارضة حسين كيانجو«إنه يجعل الرئاسة الأوغندية شأناً ملكياً وبكل وضوح يعد نجله لخلافته»، وأضاف: «هناك بالعمل حالة غضب من قبل الأوغنديين بشأن عادة الرئيس وضع أقاربه في مواقع استراتيجية، وإن ما عمله الرئيس موسيفيني يؤكد أسوأ المخاوف لدي الأوغنديين من أنه يتجه لجعل الرئاسة الأوغندية شأناً ملكياً ويعمل بوضوح علي إعداد نجله لخلافته.

وفي رد يشبه مبررات جميع الأنظمة الديكتاتورية رفض المتحدث باسم الجيش الانتقادات التي وجهتها المعارضة، ونطق «إن موهوزي لم يهجرب أي جريمة لكونه نجل الرئيس.. إنه فرد أوغندي له جميع الحقوق كمواطن ومنها المنافسة علي منصب الرئيس إذا رغب في ذلك، وأن قرار وضع لواء الحرس الرئاسي تحت قيادة وحدة القوات الخاصة التي يقودها موهوزي يأتي في إطار عملية إعادة ترتيب القوات المسلحة التي تجري حالياً».

وكان موسيفيني قد عين نجله موهوزي ـ 36 عاماً ـ رئيساً لوحدة قوات خاصة في 2008، حيث خضع لتدريبات عسكرية في بريطانيا وأمريكا، وتتولي الوحدة التي يرأسها مسئولية العمل علي منع وقوع هجمات إرهابية في البلاد وتوفير الأمن في منطقة بحيرة ألبرت التي اكتشفت بها مخزونات نفطية هائلة.

الهوامش

- ^ Sources are divided on Museveni's exact year and place of birth. While the year of 1944 is the most prominent in discourse on Museveni (Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com[], Encarta and Columbia Encyclopedia), 1945 or 1946 have also been suggested as possible years of birth (Oloka-Onyango 2003 Project MUSE).

- ^ Different biographical sources will commonly list various birthplaces for Museveni due to reorganisation of districts in Uganda. In 1944, there were four provinces one of which was Western, encompassing Museveni's birthplace. By 1966, there were 19 administrative divisions, including the Ankole kingdom. In 1976, the districts became provinces. Southern province encompassed both Ankole and Kigezi and had Mbarara as a capital. In 1989, theعشرة provinces were reorganized into 33 districts, one of which was Mbarara, and in 1994 the district of Ntungamo was formed from parts of Mbarara and Bushenyi. Museveni's birthplace has fallen, at various times, in administrative regions known as Western, Ankole, Southern, Mbarara and Ntungamo, without any contradiction. The article is reflecting the most recent region, Ntungamo. (Source: Statoids). The following sources are up to date in the respect that they give Museveni's birthplace as Ntungamo: Encyclopedia.com[], Encarta, Norwegian Council for Africa and Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ^ شبكة النبأ الإسلامية

- ^ "Causes and consequences of the war in Acholiland", Ogenga Otunnu, from Lucima et al., 2002

- ^ "Profiles of the parties to the conflict", Balam Nyeko and Okello Lucima, from Lucima et al., 2002

- ^ CIA Factbook - Uganda

- ^ Uganda, 1979–85: Leadership in Transition, Jimmy K. Tindigarukayo, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 26, No. 4. (Dec., 1988), pp. 619. (JSTOR)

- ^ "Kampala troops flee guerrilla attacks", The Times, 23 January 1986

- ^ "Troops from Zaire step up Uganda civil war", The Guardian, 21 January 1986

- ^ "Museveni sworn in as President", The Times, 30 January 1986

- ^ "Structural Adjustment in Uganda"

- ^ "Africa’s child soldiers", Daily Times, 30 May 2002

- ^ "Uganda: A Killer Before She Was Nine", Sunday Times, 15 December 2002

- ^ Uganda:Breaking the Circle", Amnesty International, 17 March 1999

- ^ Leone, Daniel A., ed. Responding to the AIDS Epidemics. Farmington Hills: Greenhaven press, 2008.

- ^ "Uganda: Heavily Indebted Poor Country Initiative (HIPC)", World Bank

- ^ "Gender implications for opening up political parties in Uganda", Dr. Sylvia Tamale, Faculty of Law, Makerere University, from the Women of Uganda Network

- ^ Uganda Leader Stands Tall in New African Order, James C. McKinley, New York Times, 15 June 1997

-

^ "Albright in Africa: The Embraceable Regimes?". The New York Times. 1997-12-16. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Explaining Ugandan intervention in Congo: evidence and interpretations", John F. Clark, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 39, pp. 267–268, 2001 (Cambridge Journals)

- ^ ibid. pp. 262–263 (Cambridge Journals)

- ^ "Uganda and Rwanda: friends or enemies?", International Crisis Group, Africa Report No. 14, أربعة May 2000

- ^ New Vision, 26 and 28 August 1998

- ^ "L'Ouganda et les guerres Congolaises", Politique Africaine, 75: 43–59, 1999

- ^ "Armed Activities on the Territory of the Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda)"[], ICJ Press Release, 19 December 2005

- ^ "'Boda-boda' men keep Museveni in driving seat", Telegraph, 13 August 2005

- ^ "State of Pain:Torture in Uganda" - Part III, Human Rights Watch

- ^ "Press release: FDC Position on amending article 105(2) of the constitution", Forum for Democratic Change, 27 June 2005

- ^ "The Travails and Antics of Africa's "Big Men" - How Power Has Corrupted African Leaders", Wafula Okumu, The Perspective, 11 April 2002

- ^ "Ugandans march against Bob Geldof", BBC News, 22 March 2005

- ^ "Uganda: An African Success Turning Sour", Johnnie Carson, speech delivered at the Wilson Center, 2 June 2005

- ^ "A threat to Africa's success story", Johnnie Carson, Boston Globe, 1 May 2005

- ^ "Norway cuts aid to Uganda over political concerns", Reuters, 19 July 2005

- ^ "Uganda: Key Opposition MPs Arrested", Human Rights Watch, 27 April 2005

- ^ "World Bank may cut aid", Paul Busharizi, New Vision, 17 May 2005

- ^ "Museveni advises donors", New Vision, 27 May 2005

- ^ "Donors Fear Me, Says Museveni", Frank Nyakairu, The Monitor, 26 May 2005

- ^ Uganda: Nation decides on political parties, UNOCHA-IRIN, 27 July 2005

- ^ "Uganda backs return to multiparty politics", Reuters, 30 July 2005

- ^ "Referendum ends 20-year ban on political parties", Reuters, 1 August 2005

- ^ "Museveni warns press over Garang", BBC,عشرة August 2005

- ^ "Banned Ugandan radio back on air", BBC, 19 August 2005

- ^ "Uganda riots over treason charge", BBC, 14 November 2005

- ^ "Col Besigye Case Opens", New Vision, 16 November 2005

- ^ "Sweden withholds Uganda aid due to democracy worry"[], Reuters, 19 December 2005

- ^ "Netherlands withholdsستة mln euros aid to Uganda", Reuters, 30 November 2005

- ^ "Uganda's Museveni wins election", BBC, 25 February 2006

- ^ [1], Rachel Maddow Show transcript, 30 November 2009.

- ^ "The Secret Political Reach of 'The Family'", NPR Fresh Air transcript, 24 November 2009.

- ^ "Harper lobbies Uganda on anti-gay bill", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), 29 November 2009.

- ^ "British PM against anti-gay legislation", Monitor Online, 29 November 2009

- ^ "Uganda considers death sentence for gay sex in bill before parliament", Guardian, 29 November 2009.

- ^ "«معاريف»: رئيس أوغندا يهدي «نجاد» نسخة من التوراة". المصري اليوم. 2011-11-17.

- ^ "يوري موسيفيني .. آفة التوريث". جريدة الدستور المصرية. 2010-03-8. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

انظر أيضا

- اوغندا

- اوغندا منذ 1979، جزء من سلسة تاريخ اوغندا.

- رئيس اوغندا

- سياسة اوغندا

- الأحزاب السياسية الاوغندية

- مؤتمر طوكيوحول تنمية أفريقيا

المصادر

| مشاع الفهم فيه ميديا متعلقة بموضوع Yoweri Museveni. |

خط

- Museveni, Yoweri. Sowing the Mustard Seed: The Struggle for Freedom and Democracy in Uganda, Macmillan Education, 1997, ISBN 0-333-64234-1.

- Museveni, Yoweri. What Is Africa's Problem?, University of Minnesota Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8166-3278-2

- Ondoga Ori Amaza, Museveni's Long March from Guerrilla to Statesman, Fountain Publishers, ISBN 9970-02-135-4

مواقع إلكترونية

- The War in the Bush, GlobalSecurity.org

- Elections in Uganda, African Elections Database

- Third term bid irks donors, News from Africa, 12 May 2005

- Human Rights Watch

- Press Freedom in Uganda

- Profile: President Yoweri Museveni, BBC News, 1 March 2001

- In Uganda, when does brash talk radio become sedition?, Christian Science Monitor, 23 August 2005

- Buganda and Uganda news website

أوراق بحثية أكاديمية

- Uganda, 1979–85: Leadership in Transition, Jimmy K. Tindigarukayo, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 26, No. 4. (Dec., 1988), pp. 607–622. (JSTOR)

- Neutralising the Use of Force in Uganda: The Role of the Military in Politics, E. A. Brett, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1. (Mar., 1995), pp. 129–152. (JSTOR)

- Called to Account: How African Governments Investigate Human Rights Violations, Richard Carver, African Affairs, Vol. 89, No. 356. (Jul., 1990), pp. 391–415. (JSTOR)

- Uganda after Amin: The Continuing Search for Leadership and Control, Cherry Gertzel, African Affairs, Vol. 79, No. 317. (Oct., 1980), pp. 461–489. (JSTOR)

- Social Disorganisation in Uganda: Before, during, and after Amin, Aidan Southall, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 18, No. 4. (Dec., 1980), pp. 627–656. (JSTOR)

- Ugandan Relations with Western Donors in the 1990s: What Impact on Democratisation?, Ellen Hauser, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 37, No. 4. (Dec., 1999), pp. 621–641. (JSTOR)

- Reading Museveni: Structure, Agency and Pedagogy in Ugandan Politics, Ronald Kassimir, Canadian Journal of African Studies, Vol. 33, No. 2/3, Special Issue: French-Speaking Central Africa: Political Dynamics of Identities and Representations. (1999), pp. 649–673. (JSTOR)

- Uganda: The Making of a Constitution, Charles Cullimore, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 32, No. 4. (Dec., 1994), pp. 707–711. (JSTOR)

- Uganda's Domestic and Regional Security since the 1970s, Gilbert M. Khadiagala, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 31, No. 2. (Jun., 1993), pp. 231–255. (JSTOR)

- Exile, Reform, and the Rise of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, Wm. Cyrus Reed, The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 34, No. 3. (Sep., 1996), pp. 479–501. (JSTOR)

- Operationalising Pro-Poor Growth, A Country Case Study on Uganda, John A. Okidi, Sarah Ssewanyana, Lawrence Bategeka, Fred Muhumuza, October 2004

- "New-Breed" Leadership, Conflict, and Reconstruction in the Great Lakes Region of Africa: A Sociopolitical Biography of Uganda's Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, Joseph Oloka-Onyango, Africa Today - Volume 50, Number 3, Spring 2004, pp. 29–52 (Project MUSE)

- "No-Party Democracy" in Uganda, Nelson Kasfir, Journal of Democracy - Volume 9, Number 2, April 1998, pp. 49–63 (Project MUSE)

- "Explaining Ugandan intervention in Congo: evidence and interpretations", John F. Clark, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 39: 261–287, 2001 (Cambridge Journals)

- "Uganda's 'Benevolent' Dictatorship"[], J. Oloka-Onyango, University of Dayton website

- "The Uganda Presidential and Parliamentary Elections 1996", James Katorobo, No. 17, Les Cahiers d'Afrique de l'est

- "Hostile to Democracy: The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda", Peter Bouckaert, Human Rights Watch, 1 October 1999

- [2] "Uganda: From one party to multi-party and beyond", Ronald Elly Wanda, The Norwegian Council for Africa, October 2005.

-

Protracted conflict, elusive peace - Initiatives to end the violence in northern Uganda, editor Okello Lucima, Accord issue 11, Conciliation Resources, 2002

- Profiles of the parties to the conflict, Balam Nyeko and Okello Lucima

- Reaching the 1985 Nairobi Agreement, Bethuel Kiplagat

لقاءات

- A Conversation with Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, Council on Foreign Relations, 21 September 2005

- Murray Oliver CTV interview (related article), August 2002

- IRIN interview,تسعة June 2005

- BBC Talking Point, July 2005

وصلات خارجية

- Presidency State House Official Website

- Official website - www.museveni.co.ug

- Museveni profile on NNDB

- Is Museveni a Revolutionary Or Mercenary? by Sam Mugumya, April 15 2009

| مناصب سياسية | ||

|---|---|---|

| سبقه غير معروف |

وزير الدفاع 1979 |

تبعه Godfrey Binaisa |

| سبقه غير معروف |

وزير التعاون الاقليمي 1979 – 1980 |

تبعه غير معروف |

| سبقه تأسيس المنصب |

نائب رئيس اللجنة الرئاسية 1979 |

تبعه إلغاء المنصب |

| سبقه تيتوأوكيلو |

رئيس أوغندا {{{start – الحاضر |

الحالي |

| مناصب عسكرية | ||

| سبقه تيتوأوكيلو |

رئيس أركان الجيش الأوغندي First NRA then renamed UPDF {{{start – الحاضر |

الحالي |

| رؤساء اوغندا | |

|---|---|

| Edward Mutesa II • ميلتون اوبوتي • عيدي أمين • يوسف لولي • Godfrey Binaisa • Paulo Muwanga • Presidential Commission • ميلتون اوبوتي • Bazilio Olara-Okello • تيتواوكيلو• يويري موسڤيني |