كابل اتصالات بحري

كابل الاتصالات البحري Submarine Communications Cable هوكابل مـُمـَدد تحت سطح البحر ليحمل اتصالات بين الدول. أول كابلات الاتصالات البحرية، في ع1850، كانت تحمل اشارات التلغراف. الأجيال اللاحقة من الكابلات حملت أولاً اشارات الاتصال الهاتفي, ثم اشارات الاتصالات الرقمية. وكل الكابلات المعاصرة تستخدم تكنولوجيا الألياف الضوئية لنقل حمولات رقمية, التي تستعمل لحمل اشارات الهاتف وكذلك الانترنت وخطوط البيانات الخاصة . وهذه الكابلات في المعتاد يبلغ قطرها نحو 69 مم وتزن نحوعشرة كج للمتر, بالرغم من استخدام كابلات أحمل وأخف للأقسام المارة في المياه العميقة.

Modern cables are typically about 1 بوصة (25 mم) in diameter and weigh around 2.5 tons per mile (1.4 tonnes per km) for the deep-sea sections which comprise the majority of the run, although larger and heavier cables are used for shallow-water sections near shore. Submarine cables first connected all the world's continents (except Antarctica) when Java was connected to Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia in 1871 in anticipation of the completion of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line in 1872 connecting to Adelaide, South Australia and thence to the rest of Australia. Africa was much earlier; 1854 Italy to Tunisia (Huurdeman, p. 137)

وبحلول عام 2003، فقد ربطت كابلات الاتصالات البحرية جميع قارات العالم ما عدا القارة القطبية الجنوبية.

Early history: telegraph and coaxial cables

First successful trials

After William Cooke and Charles Wheatstone had introduced their working telegraph in 1839, the idea of a submarine line across the Atlantic Ocean began to be thought of as a possible triumph of the future. Samuel Morse proclaimed his faith in it as early as 1840, and in 1842, he submerged a wire, insulated with tarred hemp and India rubber, in the water of New York Harbor, and telegraphed through it. The following autumn, Wheatstone performed a similar experiment in Swansea Bay. A good insulator to cover the wire and prevent the electric current from leaking into the water was necessary for the success of a long submarine line. India rubber had been tried by Moritz von Jacobi, the Prussian electrical engineer, as far back as the early 19th century.

Another insulating gum which could be melted by heat and readily applied to wire made its appearance in 1842. Gutta-percha, the adhesive juice of the Palaquium gutta tree, was introduced to Europe by William Montgomerie, a Scottish surgeon in the service of the British East India Company. Twenty years earlier, Montgomerie had seen whips made of gutta-percha in Singapore, and he believed that it would be useful in the fabrication of surgical apparatus. Michael Faraday and Wheatstone soon discovered the merits of gutta-percha as an insulator, and in 1845, the latter suggested that it should be employed to cover the wire which was proposed to be laid from Dover to Calais. It was tried on a wire laid across the Rhine between Deutz and Cologne.[] In 1849, C.V. Walker, electrician to the South Eastern Railway, submerged a two-mile wire coated with gutta-percha off the coast from Folkestone, which was tested successfully.

First commercial cables

In August 1850, having earlier obtained a concession from the French government, John Watkins Brett's English Channel Submarine Telegraph Company laid the first line across the English Channel, using the converted tugboat Goliath. It was simply a copper wire coated with gutta-percha, without any other protection, and was not successful. However, the experiment served to secure renewal of the concession, and in September 1851, a protected core, or true, cable was laid by the reconstituted Submarine Telegraph Company from a government hulk, Blazer, which was towed across the Channel.

In 1853, more successful cables were laid, linking Great Britain with Ireland, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and crossing The Belts in Denmark. The British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company completed the first successful Irish link on May 23 between Portpatrick and Donaghadee using the collier William Hutt. The same ship was used for the link from Dover to Ostend in Belgium, by the Submarine Telegraph Company. Meanwhile, the Electric & International Telegraph Company completed two cables across the North Sea, from Orford Ness to Scheveningen, the Netherlands. These cables were laid by Monarch, a paddle steamer which later became the first vessel with permanent cable-laying equipment.

In 1858, the steamship Elba was used to lay a telegraph cable from Jersey to Guernsey, on to Alderney and then to Weymouth, the cable being completed successfully in September of that year. Problems soon developed with eleven breaks occurring by 1860 due to storms, tidal and sand movements, and wear on rocks. A report to the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1860 set out the problems to assist in future cable laying operations.

Transatlantic telegraph cable

The first attempt at laying a transatlantic telegraph cable was promoted by Cyrus West Field, who persuaded British industrialists to fund and lay one in 1858. However, the technology of the day was not capable of supporting the project; it was plagued with problems from the outset, and was in operation for only a month. Subsequent attempts in 1865 and 1866 with the world's largest steamship, the , used a more advanced technology and produced the first successful transatlantic cable. Great Eastern later went on to lay the first cable reaching to India from Aden, Yemen, in 1870.

British dominance of early cable

From the 1850s until 1911, British submarine cable systems dominated the most important market, the North Atlantic Ocean. The British had both supply side and demand side advantages. In terms of supply, Britain had entrepreneurs willing to put forth enormous amounts of capital necessary to build, lay and maintain these cables. In terms of demand, Britain's vast colonial empire led to business for the cable companies from news agencies, trading and shipping companies, and the British government. Many of Britain's colonies had significant populations of European settlers, making news about them of interest to the general public in the home country.

British officials believed that depending on telegraph lines that passed through non-British territory posed a security risk, as lines could be cut and messages could be interrupted during wartime. They sought the creation of a worldwide network within the empire, which became known as the All Red Line, and conversely prepared strategies to quickly interrupt enemy communications. Britain's very first action after declaring war on Germany in World War I was to have the (not the CS Telconia as frequently reported) cut the five cables linking Germany with France, Spain and the Azores, and through them, North America. Thereafter, the only way Germany could communicate was by wireless, and that meant that Room 40 could listen in.

The submarine cables were an economic benefit to trading companies, because owners of ships could communicate with captains when they reached their destination and give directions as to where to go next to pick up cargo based on reported pricing and supply information. The British government had obvious uses for the cables in maintaining administrative communications with governors throughout its empire, as well as in engaging other nations diplomatically and communicating with its military units in wartime. The geographic location of British territory was also an advantage as it included both Ireland on the east side of the Atlantic Ocean and Newfoundland in North America on the west side, making for the shortest route across the ocean, which reduced costs significantly.

A few facts put this dominance of the industry in perspective. In 1896, there were thirty cable-laying ships in the world, twenty-four of which were owned by British companies. In 1892, British companies owned and operated two-thirds of the world's cables and by 1923, their share was still 42.7 percent. During World War I, Britain's telegraph communications were almost completely uninterrupted, while it was able to quickly cut Germany's cables worldwide.

Cable to India, Singapore, Far East and Australia

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, British cable expanded eastward, into the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean. An 1863 cable to Bombay, India (now Mumbai) provided a crucial link to Saudi Arabia. In 1870, Bombay was linked to London via submarine cable in a combined operation by four cable companies, at the behest of the British Government. In 1872, these four companies were combined to form the mammoth globe-spanning Eastern Telegraph Company, owned by John Pender. A spin-off from Eastern Telegraph Company was a second sister company, the Eastern Extension, China and Australasia Telegraph Company, commonly known simply as "the Extension". In 1872, Australia was linked by cable to Bombay via Singapore and China and in 1876, the cable linked the British Empire from London to New Zealand.

Submarine cables across the Pacific

The first trans-Pacific cables providing telegraph service were completed in 1902 and 1903, linking the US mainland to Hawaii in 1902 and Guam to the Philippines in 1903. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Fiji were also linked in 1902 with the trans-Pacific segment of the All Red Line. Japan was connected into the system in 1906. Service beyond Midway Atoll was abandoned in 1941 because of WWII, but the remainder remained in operation until 1951 when the FCC gave permission to cease operations.

The first trans-Pacific telephone cable was laid from Hawaii to Japan in 1964, with an extension from Guam to The Philippines. Also in 1964, the Commonwealth Pacific (COMPAC) cable, with 80 telephone channel capacity, opened for traffic from Sydney to Vancouver, and in 1967, the South East Asia Commonwealth (SEACOM) system, with 160 telephone channel capacity, opened for traffic. This system used microwave radio from Sydney to Cairns (Queensland), cable running from Cairns to Madang (Papua New Guinea), Guam, Hong Kong, Kota Kinabalu (capital of Sabah, Malaysia), Singapore, then overland by microwave radio to Kuala Lumpur. In 1991, the North Pacific Cable system was the first regenerative system (i.e. with repeaters) to completely cross the Pacific from the US mainland to Japan. The US portion of NPC was manufactured in Portland, Oregon, from 1989 to 1991 at STC Submarine Systems, and later Alcatel Submarine Networks. The system was laid by Cable & Wireless Marine on the CS Cable Venture.

Construction

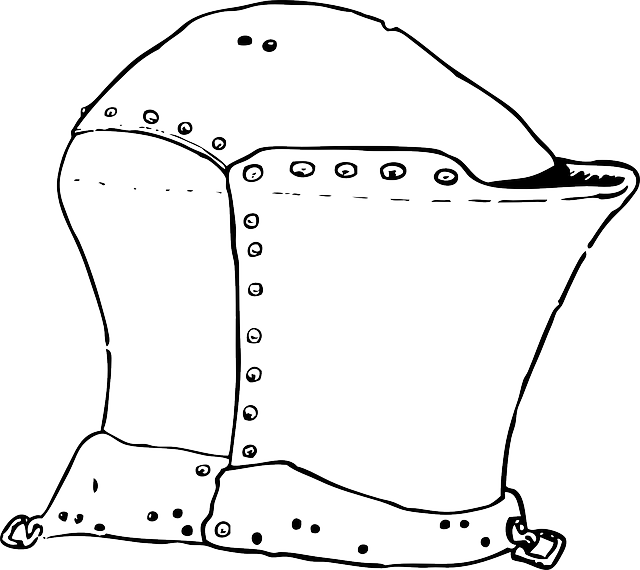

Transatlantic cables of the 19th century consisted of an outer layer of iron and later steel wire, wrapping India rubber, wrapping gutta-percha, which surrounded a multi-stranded copper wire at the core. The portions closest to each shore landing had additional protective armor wires. Gutta-percha, a natural polymer similar to rubber, had nearly ideal properties for insulating submarine cables, with the exception of a rather high dielectric constant which made cable capacitance high. Gutta-percha was not replaced as a cable insulation until polyethylene was introduced in the 1930s. Even then, the material was only available to the military and the first submarine cable using it was not laid until 1945 during World War II across the English Channel. In the 1920s, the American military experimented with rubber-insulated cables as an alternative to gutta-percha, since American interests controlled significant supplies of rubber but did not have easy access to gutta-percha manufacturers. The 1926 development by John T. Blake of deproteinized rubber improved the impermeability of cables to water.

Many early cables suffered from attack by sealife. The insulation could be eaten, for instance, by species of (shipworm) and Xylophaga. Hemp laid between the steel wire armouring gave pests a route to eat their way in. Damaged armouring, which was not uncommon, also provided an entrance. Cases of sharks biting cables and attacks by sawfish have been recorded. In one case in 1873, a whale damaged the Persian Gulf Cable between Karachi and Gwadar. The whale was apparently attempting to use the cable to clean off barnacles at a point where the cable descended over a steep drop. The unfortunate whale got its tail entangled in loops of cable and drowned. The cable repair ship Amber Witch was only able to winch up the cable with difficulty, weighed down as it was with the dead whale's body.

Bandwidth problems

Early long-distance submarine telegraph cables exhibited formidable electrical problems. Unlike modern cables, the technology of the 19th century did not allow for in-line repeater amplifiers in the cable. Large voltages were used to attempt to overcome the electrical resistance of their tremendous length but the cables' distributed capacitance and inductance combined to distort the telegraph pulses in the line, reducing the cable's bandwidth, severely limiting the data rate for telegraph operation to 10–12 words per minute.

As early as 1816, Francis Ronalds had observed that electric signals were retarded in passing through an insulated wire or core laid underground, and outlined the cause to be induction, using the analogy of a long Leyden jar. The same effect was noticed by Latimer Clark (1853) on cores immersed in water, and particularly on the lengthy cable between England and The Hague. Michael Faraday showed that the effect was caused by capacitance between the wire and the earth (or water) surrounding it. Faraday had noticed that when a wire is charged from a battery (for example when pressing a telegraph key), the electric charge in the wire induces an opposite charge in the water as it travels along. In 1831, Faraday described this effect in what is now referred to as Faraday's law of induction. As the two charges attract each other, the exciting charge is retarded. The core acts as a capacitor distributed along the length of the cable which, coupled with the resistance and inductance of the cable, limits the speed at which a signal travels through the conductor of the cable.

Early cable designs failed to analyze these effects correctly. Famously, E.O.W. Whitehouse had dismissed the problems and insisted that a transatlantic cable was feasible. When he subsequently became electrician of the Atlantic Telegraph Company, he became involved in a public dispute with William Thomson. Whitehouse believed that, with enough voltage, any cable could be driven. Because of the excessive voltages recommended by Whitehouse, Cyrus West Field's first transatlantic cable never worked reliably, and eventually short circuited to the ocean when Whitehouse increased the voltage beyond the cable design limit.

Thomson designed a complex electric-field generator that minimized current by resonating the cable, and a sensitive light-beam mirror galvanometer for detecting the faint telegraph signals. Thomson became wealthy on the royalties of these, and several related inventions. Thomson was elevated to Lord Kelvin for his contributions in this area, chiefly an accurate mathematical model of the cable, which permitted design of the equipment for accurate telegraphy. The effects of atmospheric electricity and the geomagnetic field on submarine cables also motivated many of the early polar expeditions.

Thomson had produced a mathematical analysis of propagation of electrical signals into telegraph cables based on their capacitance and resistance, but since long submarine cables operated at slow rates, he did not include the effects of inductance. By the 1890s, Oliver Heaviside had produced the modern general form of the telegrapher's equations, which included the effects of inductance and which were essential to extending the theory of transmission lines to higher frequencies required for high-speed data and voice.

الاتصالات الهاتفية عبر الأطلنطي

While laying a transatlantic telephone cable was seriously considered from the 1920s, the technology required for economically feasible telecommunications was not developed until the 1940s. A first attempt to lay a pupinized telephone cable failed in the early 1930s due to the Great Depression.

In 1942, Siemens Brothers of New Charlton, London in conjunction with the United Kingdom National Physical Laboratory, adapted submarine communications cable technology to create the world's first submarine oil pipeline in Operation Pluto during World War II.

TAT-1 (Transatlantic No. 1) was the first transatlantic telephone cable system. Between 1955 and 1956, cable was laid between Gallanach Bay, near Oban, Scotland and Clarenville, Newfoundland and Labrador. It was inaugurated on September 25, 1956, initially carrying 36 telephone channels.

In the 1960s, transoceanic cables were coaxial cables that transmitted frequency-multiplexed voiceband signals. A high voltage direct current on the inner conductor powered repeaters (two-way amplifiers placed at intervals along the cable). The first-generation repeaters remain among the most reliable vacuum tube amplifiers ever designed. Later ones were transistorized. Many of these cables are still usable, but have been abandoned because their capacity is too small to be commercially viable. Some have been used as scientific instruments to measure earthquake waves and other geomagnetic events.

Modern history

Optical telephone cables

|

|

In the 1980s, fiber optic cables were developed. The first transatlantic telephone cable to use optical fiber was TAT-8, which went into operation in 1988. A fiber-optic cable comprises multiple pairs of fibers. Each pair has one fiber in each direction. TAT-8 had two operational pairs and one backup pair.

Modern optical fiber repeaters use a solid-state optical amplifier, usually an Erbium-doped fiber amplifier. Each repeater contains separate equipment for each fiber. These comprise signal reforming, error measurement and controls. A solid-state laser dispatches the signal into the next length of fiber. The solid-state laser excites a short length of doped fiber that itself acts as a laser amplifier. As the light passes through the fiber, it is amplified. This system also permits wavelength-division multiplexing, which dramatically increases the capacity of the fiber.

Repeaters are powered by a constant direct current passed down the conductor near the center of the cable, so all repeaters in a cable are in series. Power feed equipment is installed at the terminal stations. Typically both ends share the current generation with one end providing a positive voltage and the other a negative voltage. A virtual earth point exists roughly halfway along the cable under normal operation. The amplifiers or repeaters derive their power from the potential difference across them.

The optic fiber used in undersea cables is chosen for its exceptional clarity, permitting runs of more than 100 kiloمترs (330,000 قدم) between repeaters to minimize the number of amplifiers and the distortion they cause.

The rising demand for these fiber-optic cables outpaced the capacity of providers such as AT&T.[] Having to shift traffic to satellites resulted in poorer quality signals. To address this issue, AT&T had to improve its cable laying abilities. It invested $100 million in producing two specialized fiber-optic cable laying vessels. These included laboratories in the ships for splicing cable and testing its electrical properties. Such field monitoring is important because the glass of fiber-optic cable is less malleable than the copper cable that had been formerly used. The ships are equipped with thrusters that increase maneuverability. This capability is important because fiber-optic cable must be laid straight from the stern (another factor copper cable laying ships did not have to contend with).

Originally, submarine cables were simple point-to-point connections. With the development of submarine branching units (SBUs), more than one destination could be served by a single cable system. Modern cable systems now usually have their fibers arranged in a self-healing ring to increase their redundancy, with the submarine sections following different paths on the ocean floor. One reason for this development was that the capacity of cable systems had become so large that it was not possible to completely backup a cable system with satellite capacity, so it became necessary to provide sufficient terrestrial back-up capability. Not all telecommunications organizations wish to take advantage of this capability, so modern cable systems may have dual landing points in some countries (where back-up capability is required) and only single landing points in other countries where back-up capability is either not required, the capacity to the country is small enough to be backed up by other means, or having back-up is regarded as too expensive.

A further redundant-path development over and above the self-healing rings approach is the "Mesh Network" whereby fast switching equipment is used to transfer services between network paths with little to no effect on higher-level protocols if a path becomes inoperable. As more paths become available to use between two points, the less likely it is that one or two simultaneous failures will prevent end-to-end service.

As of 2012, operators had "successfully demonstrated long-term, error-free transmission at 100 Gbps across Atlantic Ocean" routes of up to 6,000 kم (19,685,000 قدم), meaning a typical cable can move tens of terabits per second overseas. Speeds improved rapidly in the previous few years, with 40 Gbit/s having been offered on that route only three years earlier in August 2009.

Switching and all-by-sea routing commonly increases the distance and thus the round trip latency by more than 50%. For example, the round trip delay (RTD) or latency of the fastest transatlantic connections is under 60 ms, close to the theoretical optimum for an all-sea route. While in theory, a great circle route between London and New York City is only 5,600 kم (18,372,700 قدم), this requires several land masses (Ireland, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island and the isthmus connecting New Brunswick to Nova Scotia) to be traversed, as well as the extremely tidal Bay of Fundy and a land route along Massachusetts' north shore from Gloucester to Boston and through fairly built up areas to Manhattan itself. In theory, using this partial land route could result in round trip times below 40 ms, not counting switching (which is the speed of light minimum). Along routes with less land in the way, speeds can approach speed of light minimums in the long term.

Importance of submarine cables

Currently 99% of the data traffic that is crossing oceans is carried by undersea cables. The reliability of submarine cables is high, especially when (as noted above) multiple paths are available in the event of a cable break. Also, the total carrying capacity of submarine cables is in the terabits per second, while satellites typically offer only 1,000 megabits per second and display higher latency. However, a typical multi-terabit, transoceanic submarine cable system costs several hundred million dollars to construct.

As a result of these cables' cost and usefulness, they are highly valued not only by the corporations building and operating them for profit, but also by national governments. For instance, the Australian government considers its submarine cable systems to be "vital to the national economy". Accordingly, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) has created protection zones that restrict activities that could potentially damage cables linking Australia to the rest of the world. The ACMA also regulates all projects to install new submarine cables.

Submarine cables are important to the modern military as well as private enterprise. The US military, for example, uses the submarine cable network for data transfer from conflict zones to command staff in the US. Interruption of the cable network during intense operations could have direct consequences for the military on the ground.

Investment in and financing of submarine cables

Almost all fiber optic cables from TAT-8 in 1988 until approximately 1997 were constructed by "consortia" of operators. For example, TAT-8 counted 35 participants including most major international carriers at the time such as AT&T Corporation. Two privately financed, non-consortium cables were constructed in the late 1990s, which preceded a massive, speculative rush to construct privately financed cables that peaked in more than $22 billion worth of investment between 1999 and 2001. This was followed by the bankruptcy and reorganization of cable operators such as Global Crossing, 360networks, FLAG, Worldcom, and Asia Global Crossing.

There has been an increasing tendency in recent years to expand submarine cable capacity in the Pacific Ocean (the previous bias always having been to lay communications cable across the Atlantic Ocean which separates the United States and Europe). For example, between 1998 and 2003, approximately 70% of undersea fiber-optic cable was laid in the Pacific. This is in part a response to the emerging significance of Asian markets in the global economy.

Although much of the investment in submarine cables has been directed toward developed markets such as the transatlantic and transpacific routes, in recent years there has been an increased effort to expand the submarine cable network to serve the developing world. For instance, in July 2009, an underwater fiber optic cable line plugged East Africa into the broader Internet. The company that provided this new cable was SEACOM, which is 75% owned by Africans. The project was delayed by a month due to increased piracy along the coast.

Antarctica

Antarctica is the only continent not yet reached by a submarine telecommunications cable. All phone, video, and e-mail traffic must be relayed to the rest of the world via satellite links that have limited availability and capacity. Bases on the continent itself are able to communicate with one another via radio, but this is only a local network. To be a viable alternative, a fiber-optic cable would have to be able to withstand temperatures of −80 °م (−112 °ف) as well as massive strain from ice flowing up toعشرة مترs (33 قدم) per year. Thus, plugging into the larger Internet backbone with the high bandwidth afforded by fiber-optic cable is still an as-yet infeasible economic and technical challenge in the Antarctic.

Cable repair

Cables can be broken by fishing trawlers, anchors, earthquakes, turbidity currents, and even shark bites. Based on surveying breaks in the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, it was found that between 1959 and 1996, fewer than 9% were due to natural events. In response to this threat to the communications network, the practice of cable burial has developed. The average incidence of cable faults was 3.7 per 1,000 kم (3,280,840 قدم) per year from 1959 to 1979. That rate was reduced to 0.44 faults per 1,000 km per year after 1985, due to widespread burial of cable starting in 1980. Still, cable breaks are by no means a thing of the past, with more than 50 repairs a year in the Atlantic alone, and significant breaks in 2006, 2008, and 2009.

The propensity for fishing trawler nets to cause cable faults may well have been exploited during the Cold War. For example, in February 1959, a series of 12 breaks occurred in five American trans-Atlantic communications cables. In response, a United States naval vessel, the , detained and investigated the Soviet trawler Novorosiysk. A review of the ship's log indicated it had been in the region of each of the cables when they broke. Broken sections of cable were also found on the deck of the Novorosiysk. It appeared that the cables had been dragged along by the ship's nets, and then cut once they were pulled up onto the deck to release the nets. The Soviet Union's stance on the investigation was that it was unjustified, but the United States cited the Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph Cables of 1884 to which Russia had signed (prior to the formation of the Soviet Union) as evidence of violation of international protocol.

Shore stations can locate a break in a cable by electrical measurements, such as through spread-spectrum time-domain reflectometry (SSTDR). SSTDR is a type of time-domain reflectometry that can be used in live environments very quickly. Presently, SSTDR can collect a complete data set in 20 ms. Spread spectrum signals are sent down the wire and then the reflected signal is observed. It is then correlated with the copy of the sent signal and algorithms are applied to the shape and timing of the signals to locate the break.

A cable repair ship will be sent to the location to drop a marker buoy near the break. Several types of grapples are used depending on the situation. If the sea bed in question is sandy, a grapple with rigid prongs is used to plough under the surface and catch the cable. If the cable is on a rocky sea surface, the grapple is more flexible, with hooks along its length so that it can adjust to the changing surface. In especially deep water, the cable may not be strong enough to lift as a single unit, so a special grapple that cuts the cable soon after it has been hooked is used and only one length of cable is brought to the surface at a time, whereupon a new section is spliced in. The repaired cable is longer than the original, so the excess is deliberately laid in a 'U' shape on the seabed. A submersible can be used to repair cables that lie in shallower waters.

A number of ports near important cable routes became homes to specialised cable repair ships. Halifax, Nova Scotia was home to a half dozen such vessels for most of the 20th century including long-lived vessels such as the CS Cyrus West Field, CS Minia and CS Mackay-Bennett. The latter two were contracted to recover victims from the . The crews of these vessels developed many new techniques and devices to repair and improve cable laying, such as the "plough".

Intelligence gathering

Underwater cables, which cannot be kept under constant surveillance, have tempted intelligence-gathering organizations since the late 19th century. Frequently at the beginning of wars, nations have cut the cables of the other sides to redirect the information flow into cables that were being monitored. The most ambitious efforts occurred in World War I, when British and German forces systematically attempted to destroy the others' worldwide communications systems by cutting their cables with surface ships or submarines. During the Cold War, the United States Navy and National Security Agency (NSA) succeeded in placing wire taps on Soviet underwater communication lines in Operation Ivy Bells.

Environmental impact

The main point of interaction of cables with marine life is in the benthic zone of the oceans where the majority of cable lies. Studies in 2003 and 2006 indicated that cables pose minimal impacts on life in these environments. In sampling sediment cores around cables and in areas removed from cables, there were few statistically significant differences in organism diversity or abundance. The main difference was that the cables provided an attachment point for anemones that typically could not grow in soft sediment areas. Data from 1877 to 1955 showed a total of 16 cable faults caused by the entanglement of various whales. Such deadly entanglements have entirely ceased with improved techniques for placement of modern coaxial and fiber-optic cables which have less tendency to self-coil when lying on the seabed.

Security implications

Submarine cables are problematic from the security perspective because maps of submarine cables are widely available. Publicly available maps are necessary so that shipping can avoid damaging vulnerable cables by accident. However, the availability of the locations of easily damaged cables means the information is also easily accessible to criminal agents. Governmental wiretapping also presents cybersecurity issues.

Law issues

Submarine cables are suffering from the inherent issue stemming from the historically established practice of cable laying. Since the cable connection is usually done by the private consortiums, there is a problem with responsibility in the beginning. Firstly, deciding the responsibility inside consortium can prove tricky on itself, since there is not a one clearly leading company which could be designed as responsible it could lead to confusion when it is needed to decide who should be taking care about the cable. Secondly, it is hard to navigate the issue of cable damage through the international legal regime, since the regime was signed by and design for the states, not for private companies. Thus it is hard to decide who should be responsible for the damage costs and repairs, the company who built the cable, the company who paid the cable, the government from where the cable originated, or the government where the cable ends.

Another legal issue from which is the internal submarine cable regime suffering is the ageing of the legal system, for example, Australia still uses the fines which were priced during the signing of the 1884 submarine cable treaty and sides which commits transgressions over the cables are fined with, for today almost irrelevant, 2000 Australian dollars.

Influence of cable networks on modern history

Submarine communication cables have had a wide variety of influences over society. As well as allowing effective intercontinental trading and supporting stock exchanges, they greatly influenced international diplomatic conduct. Before the existence of submarine communication connection diplomats had much more power in their hands since their direct supervisors (governments of the countries which they represented) could not immediately check on them. Getting instructions to the diplomats in a foreign country often took weeks or even months. Diplomats had to use their own initiative in negotiations with foreign countries with only an occasional check from their government. This slow connection resulted in diplomats engaging in leisure activities while they waited for orders. The expansion of telegraph cables greatly reduced the response time needed to instruct diplomats. Over time, this led to a general decrease in prestige and power of individual diplomats within international politics and signalled a professionalization of the diplomatic corps who had to abandon their leisure activities.

Notable events

During testing of the TAT-8 fibre cable conducted by AT&T in the Canary Islands area, shark bite damage to the cable occurred. This revealed that sharks will dive to depths of one kilometre, a depth which surprised marine biologists who until then thought that sharks were not active at such depths.

The Newfoundland earthquake of 1929 broke a series of trans-Atlantic cables by triggering a massive undersea mudslide. The sequence of breaks helped scientists chart the progress of the mudslide.

In July 2005, a portion of the SEA-ME-WE ثلاثة submarine cable located 35 kiloمترs (114,829 قدم) south of Karachi that provided Pakistan's major outer communications became defective, disrupting almost all of Pakistan's communications with the rest of the world, and affecting approximatelyعشرة million Internet users.

On 26 December 2006, the 2006 Hengchun earthquake rendered numerous cables between Taiwan and Philippines inoperable.

In March 2007, pirates stole an 11-kiloمتر (36,089 قدم) section of the T-V-H submarine cable that connected Thailand, Vietnam, and Hong Kong, afflicting Vietnam's Internet users with far slower speeds. The thieves attempted to sell the 100 tons of cable as scrap.

The 2008 submarine cable disruption was a series of cable outages, two of the three Suez Canal cables, two disruptions in the Persian Gulf, and one in Malaysia. It caused massive communications disruptions to India and the Middle East.

In April 2010, the undersea cable SEA-ME-WE أربعة was under an outage. The South East Asia – Middle East – Western Europe أربعة (SEA-ME-WE 4) submarine communications cable system, which connects South East Asia and Europe, was reportedly cut in three places, off Palermo, Italy.

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami damaged a number of undersea cables that make landings in Japan, including:

- APCN-2, an intra-Asian cable that forms a ring linking China, Hong Kong, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Taiwan

- Pacific Crossing West and Pacific Crossing North

- Segments of the East Asia Crossing network (reported by PacNet)

- A segment of the Japan–U.S. Cable Network (reported by Korea Telecom)

- PC-1 submarine cable system (reported by NTT)

In February 2012, breaks in the EASSy and TEAMS cables disconnected about half of the networks in Kenya and Uganda from the global Internet.

In March 2013, the SEA-ME-WE-4 connection from France to Singapore was cut by divers near Egypt.

In November 2014 the SEA-ME-WE ثلاثة stopped all traffic from Perth, Australia to Singapore due to an unknown cable fault.

In August 2017, a fault in IMEWE (India-Middle East-Western Europe) undersea cable near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia disrupted the internet in Pakistan. The IMEWE submarine cable is an ultra-high capacity fiber optic undersea cable system which links India and Europe via the Middle East. The 12,091 km long cable has nine terminal stations, operated by leading telecom carriers from eight countries.

AAE-1, spanning over 25,000 kilometers, connects South East Asia to Europe via Egypt. Construction was finished in 2017.

إنقطاع الكابل

تضمنت انقطاع الكابلات البحرية عام 2008 أضراراً في نحوخمس كابلات اتصالات بحرية للانترنت فائقة السرعة في البحر المتوسط والشرق الأوسط من 23 يناير إلى أربعة فبراير 2008 مسببة انقطاع وتباطؤ خدمات الانترنت للمستخدمين في الشرق الأوسط والهند.

إصلاح الكابلات

يمكن تعطيل أوكسر الكابلات بواسطة سفن الصيد ، المراسي ، الزلازل ، تيار التعكر ، وحتى عضات سمك القرش. بناءً على فترات الاستقصاء التي جرت في المحيط الأطلنطي والبحر الكاريبي ، عثر أنه بين عامي 1959 و1996 ، كان حدوث أقل من 9٪ من الأعطال بسبب الأحداث الطبيعية. استجابة لهذا التهديد على شبكة الاتصالات ، تطورت عملية طمر الكابلات. كان متوسط معدل حدوث أعطال الكبلات 3.7 لكل 1,000 kم (3,280,840 قدم) سنويًا من 1959 إلى 1979. تم تخفيض هذا المعدل إلى 0.44 خطأ لكل 1000 كيلومتر في السنة بعد عام 1985 ، بسبب انتشار عملية طمر الكابلات ابتداء من عام 1980. ومع ذلك ، فإن انقطاع الكابلات ليس شيئًا من الماضي على الإطلاق ، مع أكثر من 50 عملية إصلاح سنويًا في المحيط الأطلسي وحده, وفترات كبيرة في 2006 ، 2008 ، و2009.

ربما تم استغلال ميل شباك الصيد بسفن الصيد لإحداث أعطال في الكابلات خلال الحرب الباردة. على سبيل المثال ، في فبراير 1959 ، سقطت سلسلة من 12 عطل في خمسة كابلات اتصالات أمريكية عبر المحيط الأطلسي. ردا على ذلك ، سفينة تابعة للبحرية الأمريكية ، [[USS Roy O. Hale (DE-336) | United States. "روي أوهيل" ،] ، اعتقلت السفينة الروسية "نوفوروسيسك" وحققت فيها. أوضحت مراجعة دخول السفينة أنه كان في منطقة جميع الكابلات التي تم تعطيلها. تم العثور على أقسام مكسورة من الكابلات أيضًا على سطح السفينة "Novorosiysk". يظهر حتى الكابلات تم سحبها بواسطة شباك السفينة ، ثم تم بترها بمجرد سحبها على سطح السفينة لتحرير الشباك. كان موقف الاتحاد السوفيتي من التحقيق أنه غير مبرر ، لكن الولايات المتحدة استشهدت بـ اتفاقية حماية كابلات التلغراف البحرية لعام 1884 التي سقطت عليها روسيا (قبل تشكيل الاتحاد السوفيتي) كدليل انتهاك البروتوكول الدولي.

يمكن لمحطات الشاطئ تحديد مسقط الكسر في الكبل عن طريق القياسات الكهربائية ، مثل من خلال قياس مدى المجال الطيفي للانعكاس (SSTDR). SSTDR هونوع من قياس انعكاس المجال الزمني الذي يمكن استخدامه في البيئات الحية بسرعة كبيرة. في الوقت الحاضر ، يمكن لـ SSTDR جمع مجموعة بيانات كاملة في 20 مللي ثانية.تم إرسال إشارات الطيف المنتشر أسفل السلك ثم تمت ملاحظة الإشارة المنعكسة. ثم تم ربطها بنسخة الإشارة المرسلة ويتم تطبيق الخوارزميات على شكل وتوقيت الإشارات لتحديد الفاصل. سيتم إرسال سفينة إصلاح كبل إلى المسقط لإسقاط العوامة كعلامة بالقرب من الفاصل. تستخدم عدة أنواع من grapples اعتمادًا على هذه الحالة . إذا كان قاع البحر المعني رمليًا ، فسيتم استخدام خطاف ذوأشواك صلبة للحرث تحت السطح والتقاط الكابل. إذا كان الكبل على سطح بحر صخري ، فإن الخطافقد يكون أكثر مرونة ، مع وجود خطافات بطول يمكن من التكيف مع السطح المتغير. في المياه العميقة بشكل خاص ، قد لاقد يكون الكبل قويًا بدرجة كافية لحمله كوحدة واحدة ، لذلك يتم استخدام خطاف خاص ببتر الكبل بعد فترة وجيزة من التوصيل ، ويتم جلب طول كبل واحد فقط إلى السطح في وقت واحد ، عندها يتم تقسيم قسم حديث فيه. الكبل الذي تم إصلاحه أطول من الأصل ، لذلك تم وضع الفائض بشكل متعمد على شكل حرف "U" في قاع البحر. يمكن استعمال الغاطسة لإصلاح الكابلات الموجودة في المياه الضحلة.

أصبح عدد من الموانئ بالقرب من طرق الكابلات المهمة بمثابة منازل لسفن إصلاح الكابلات المتخصصة. هاليفاكس ، نوفا سكوشيا كانت موطنًا لنصف دزينة من هذه السفن في معظم القرن العشرين بما في ذلك السفن طويلة العمر مثل CS Cyrus West الحقل "" وCS "" المنيا "و" "CS Mackay-Bennett" ". تم التعاقد مع الأخيرين لاستعادة الضحايا من . طورت أطقم هذه السفن الكثير من التقنيات والأجهزة الجديدة لإصلاح وتحسين أعطى الكابلات ، مثل " and plow | cable plow | plough".

أصحاب ومشغلوالسفن الممددة للكابلات

- NSW New South Wales

- ASN Marine

- Elettra; أليترا

- فرانس تليكوم البحرية FT Marine

- Global Marine Systems Limited النظم البحرية العالمية المحدودة

- شركة الاتصالات اليابانية الحكومية NTT World Engineering Marine Corporation (NTT-WEM)

- S. B. Submarine Systems اأنظمة الغواصات

- YIT Primatel Ltd. هي أكبر شركة بناء في شمال أوروبا وفنلندا.

- E-MARINE

- IT International Telecom Inc. تكنولوجيا المعلومات الدولية للاتصالات

- Subsea 7.

الولوج لبيانات الكابلات

لدى الحكومة الأمريكية مشكلة: التجسس في العصر الرقمي يحتاج الولوج لكابلات الألياف الضوئية الموجودة في قاع محيطات العالم، ناقلة في سرعة الضوء سيول من البيانات. واحد من أكبر مشغلي هذه الكابلات تم بيعه لشركة آسيوية، من المحتمل حتى تعيق الجهود الأمريكية في المراقبة.

في محادثات خاصة استمرت لمدة شهر، قام فريق من محامي الإف بي أي ووزارات الدفاع، العدل والأمن الوطني بمطالبة الشركة بالحفااظ على ما حصلت عليه الوحدة الداخلية بالشركة والخاص بالمواطنين الأمريكية بتصريح من الحكومة الأمريكية. من خلال وظائفهم، عرض الوثائق، تم التأكد من أنه تم إنجاز متطلبات المراقبة بسرعة وسرية.

تم التوقيع على "اتفاقية أمن الشبكة"، في سبتمبر 2003 مع شركة گلوبال كروسينگ، ليصبح نموذج للاتفاقيات الأخرى التي سقطت في العقد الماضي، في الوقت الذي تزايد استحواذ المستثمرين الأجانب على البنية التحتية للاتصالات بالعالم.

الاتفاقيات متاحة للعامة حيث تعتبر نافذة على الجهود التي يبذلها الموظفون الأمريكيون لحماية قدرتهم على المراقبة عن طريق شبكات الألياف الضوئية التي تعمل كم هائل من البيانات الصوتية والحركة على الإنترنت في العالم.

الاتفاقيات، التي كان الغرض الرئيسي منها تأمين شبكات الاتصالات الأمريكية من التجسس الأجنبي، لكنها لا تسمح بالتجسس. لكنها تضمن أنه في الوقت الذي بحاجة فيه الوكالات الحكومية الأمريكية الولوج إلى عدد ضخم من البيانات المارة عبر شبكاتها، يتوافر في الشركات نظم لتوفير ذللك بشكل آمن، كما اتى على لسان أشخاص مطلعون على تلك الاتفاقيات.

Negotiating leverage has come from a seemingly mundane government power: the authority of the Federal Communications Commission to approve cable licenses. In deals involving a foreign company, say people familiar with the process, the FCC has held up approval for many months while the squadron of lawyers dubbed Team Telecom developed security agreements that went beyond what’s required by the laws governing electronic eavesdropping.

The security agreement for Global Crossing, whose fiber-optic network connected 27 nations and four continents, required the company to have a “Network Operations Center” on U.S. soil that could be visited by government officials with 30 minutes of warning. Surveillance requests, meanwhile, had to be handled by U.S. citizens screened by the government and sworn to secrecy — in many cases prohibiting information from being shared even with the company’s executives and directors.

“Our telecommunications companies have no real independence in standing up to the requests of government or in revealing data,” said Susan Crawford, a Yeshiva University law professor and former Obama White House official. “This is yet another example where that’s the case.”

The full extent of the National Security Agency’s access to fiber-optic cables remains classified. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence issued a statement saying that legally authorized data collection “has been one of our most important tools for the protection of the nation’s — and our allies’ — security. Our use of these authorities has been properly classified to maximize the potential for effective collection against foreign terrorists and other adversaries.”

تجسس وكالة المخابرات القومية

إدوارد سنودن، مقاول لصالح وكالة الأمن القومي قبل الكشف للإعلام عن التفاصيل السرية لبرنامج التجسس الخاص بالوكالة.، نطق في تسريباته الأخيرة حتى شركات التكنولوجيا مثل گوگل وميكروسوفت ليست فقط تتعاون بطيب خاطر مع الأجهزة الأمنية - لكنها تساعد نفسها أيضاً، حيث تقوم بالتصنت على الإنترنت، والولوج لكميات هائلة من البيانات من الكابلات البحرية.

يوضح تقرير نشر في أتلانتيك كيف من الممكن أن يتجسس البريطانيون باستخدام أكثر من برنامجين صوتيتين أسماء "گلوبال تلكومز إكسپلوريشن" و"ماسترينگ ذه إنترنت". ينطق حتى هذه البرامج تشبه برنامج پريزم، ويتم تشغيلهم تحت عملية كبرى تسمى "مشروع تمپورا". حسب الوثائق المسربة من سنودن، عن طريق تمپورا يتم تجميع أكثر من 21 مليون گيگابايت من البيانات يومياً، والتي يم تجميعها وتحليلها في جهة واحدة.

وصفت الأتلانتيك كيف من الممكن أن حتى تلك البيانات يتم تقاسمها بين مقرات الاتصالات الحكومية البريطانية وناسا، حيث يعمل أكثر من 550 محلل بدوام تام على تصنيفها وتحليلها. في هذه الحالة، فإن الخطر على خصوصيتنا أكثر مما تجمعه ناسا عن پريزم، لأن التصنت على الكابلات البحرية يعني حتى الوكالات يمكنها جمع المحتويات الدخلية للاتصالات، أكثر من مجرد حصولها على بيانات وصفية.

متحدثاً إلى محلل الأمن ياكون أپلبوم، يروي سنودن كيف من الممكن أن حتى مقرات الاتصالات الحكومية البريطانية "يمكن حتى تكون أسوأ" من ناسا، لأن أنظمتها تقوم بإفراغ جميع البيانات دون تمييز، بغض النظر عن كونها تخص من أوعن محتوى تلك البيانات.

يقول سنودن "إذا كن لديك إختيار، يجب عليك ألا ترسل أي بيانات عن طريق الخطوط أوالخوادم البريطانية".

الطريقة العملية التي تستخدم مقرات الاتصالات الحكومية البريطانية للحصول على هذه البيانات لا يزال محل جدل، بالرغم من حتى الأتلانتيك تعتقد أنه يمكن حتىقد يكون عن طريق نوع من "المسبارات الاعتراضية" الذي يتم وضعه في مختلف المحطات الأرضية بالمملكة المتحدة. هذه "المسبارات الاعتراضية" ينطق أنها أجهزة صغيرة قادرة على إلتقاط الضوء المرسل إلى كابلات الألياف البصرية، فيقوم الضوء حول "پريزم"، بنسخها، قبل السماح لها في الاستمرار في طريقها.

مقاول الحكومة الأمريكية گيلمرگلاس، من المرجح أنه قدم على الأقل بعض من تلك التكنولوجيات التي سمحت لمقرات الاتصالات الحكومية البريطانية بهذا التصنت. أفادت أڤياشن ويك حتى الشركات كانت تقوم ببعض الإعتراضات لصالح مقرات الاتصالات الحكومية، لصالح الحكومة الأمريكية في 2010. علاوة على ذلك، فقد تجاوز وأن تفاخر گيلمرگلاس بأنه كان قادراً على مراقبة حركة الخدمات وتضم فيسبوك وجيميل، ونطق أنه باع هذه التكنولوجيا لمختلف الحكومات.

حوادث

حسب مسقط دبكة الإسرائيلي، فإن الحريق الذي نشب في 1 يوليوداخل غواصة نووية روسية من طراز AS-12 Losharik، متخصصة في بتر كابلات الإنترنت والتنصت عليها، اغتال 14 مختص متميز، وقع بمياه ولاية ألاسكا الأمريكية. غواصة أمريكية اعترضتها وأطلقت النار. فأطلقت غواصة روسية مصاحبة طوربيد من طراز بلقان-2000 أغرق الغواصة الأمريكية. البلدان يتكتمان، لحساسية التفاصيل.

القتلى الروس 14 مختص فريد، بعضهم حاصل على لقب "بطل روسيا الاتحادية". عقد پوتن اجتماع عاجل مع وزير الدفاع، وترمب أمر نائبه ببتر رحلته والعودة فوراً للتشاور.

الغواصة لوشاريك صُممت في عقد الثمانينيات، ودُشنت في 2003، إلا حتى تفاصيل قدراتها هي من الأسرار. ويبلغ عدد طاقمها 25 فرد، وتعمل على عمق يزيد على 3,300 متر تحت سطح الماء. وهذا النوع من الغواصات قد يُستخدم في غرس أوتعطيل مصفوفات سونار في قاع المحيط. وهذه المهمة تتفق مع بيان وزارة الدفاع الروسية حتى النار شبت أثناء عمل الغواصة مسح باثيمتري (لقاع المحيط) لقياس الأعماق.

معرض الصور

انظر ايضاً

- قائمة كابلات الاتصالات البحرية الدولية

- قائمة كابلات الاتصالات البحرية الاقليمية

- كابل التلغراف العابر للأطلنطي

- كابل الهاتف العابر للأطلنطي

- ألياف ضوئية

- Loaded submarine cable

- Submarine power cable

- Cable layer

- Bathometer

- انقطاع الكابلات البحرية عام 2008

المصادر

- ^ خريطة حوادث بتر الكابلات

- ^ "How Submarine Cables are Made, Laid, Operated and Repaired", TechTeleData

- ^ "The internet's undersea world" Archived 2010-12-23 at the Wayback Machine. – annotated image, The Guardian.

- ^ Anton A. Huurdeman, The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, pp. 136–140, John Wiley & Sons, 2003 ISBN 0471205052.

- ^ [Heroes of the Telegraph – Chapter III. – Samuel Morse] "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved 2008-02-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- ^ "Timeline – Biography of Samuel Morse". Inventors.about.com. 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ Haigh, Kenneth Richardson (1968). Cable Ships and Submarine Cables. London: Adlard Coles. ISBN .

- ^ Guarnieri, M. (2014). "The Conquest of the Atlantic". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 8 (1): 53–56/67. doi:10.1109/MIE.2014.2299492.

- ^ The company is referred to as the English Channel Submarine Telegraph Company

- ^ Brett, John Watkins (March 18, 1857). "On the Submarine Telegraph". Royal Institution of Great Britain: Proceedings (transcript). II, 1854–1858. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ^ Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. p. 26.

- ^ Kennedy, P. M. (October 1971). "Imperial Cable Communications and Strategy, 1870–1914". The English Historical Review. 86 (341): 728–752. doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxvi.cccxli.728. JSTOR 563928.

- ^ Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, In Spies We Trust: The Story of Western Intelligence, page 43, Oxford University Press, 2013 ISBN 0199580979.

- ^ Jonathan Reed Winkler, Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I, pages 5–6, 289, Harvard University Press, 2008 ISBN 0674033906.

- ^ Headrick, D.R., & Griset, P. (2001). Submarine telegraph cables: business and politics, 1838–1939. The Business History Review, 75(3), 543–578.

- ^ "The Telegraph – Calcutta (Kolkata) | Frontpage | Third cable cut, but India's safe". Telegraphindia.com. 2008-02-03. Archived from the original on 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ Landing the New Zealand cable, pg 3, The Colonist, 19 February 1876

- ^ "Pacific Cable (SF, Hawaii, Guam, Phil) opens, President TR sends message July أربعة in History". Brainyhistory.com. 1903-07-04. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "History of Canada-Australia Relations". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 2014-07-20. Retrieved 2014-07-28.

- ^ "The Commercial Pacific Cable Company". atlantic-cable.com. Atlantic Cable. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ "Milestones:TPC-1 Transpacific Cable System, 1964". ethw.org. Engineering and Technology History WIKI. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- ^ Ash, Stewart, "The development of submarine cables", ch. 1 in, Burnett, Douglas R.; Beckman, Robert; Davenport, Tara M., Submarine Cables: The Handbook of Law and Policy, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2014 ISBN 9789004260320.

- ^ Blake, J. T.; Boggs, C. R. (1926). "The Absorption of Water by Rubber". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 18 (3): 224–232. doi:10.1021/ie50195a002.

- ^ "On accidents to submarine cables", Journal of the Society of Telegraph Engineers, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 311–313, 1873

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN .

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (Feb 2016). "The Bicentennial of Francis Ronalds's Electric Telegraph". Physics Today. 69 (2): 26–31. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3079.

- ^ "Learn About Submarine Cables". International Submarine Cable Protection Committee. Archived from the original on 2007-12-13.. From this page: In 1966, after ten years of service, the 1608 tubes in the repeaters had not suffered a single failure. In fact, after more than 100 million tube-hours over all, AT&T undersea repeaters were without failure.

- ^ Butler, R.; A. D. Chave; F. K. Duennebier; D. R. Yoerger; R. Petitt; D. Harris; F.B. Wooding; A. D. Bowen; J. Bailey; J. Jolly; E. Hobart; J. A. Hildebrand; A. H. Dodeman. "The Hawaii-2 Observatory (H2O)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-02-26.

- ^ Bradsher, K. (1990, August 15). New fiber-optic cable will expand calls abroad, and defy sharks. The New York Times, D7

- ^ "Submarine Cable Networks – Hibernia Atlantic Trials the First 100G Transatlantic". Submarinenetworks.com. Archived from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "Light Reading Europe – Optical Networking – Hibernia Offers Cross-Atlantic 40G – Telecom News Wire". Lightreading.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-29. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "Great Circle Mapper". Gcmap.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-25. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "Undersea Cables Transport 99 Percent of International Data". Newsweek. Retrieved 2016-11-16.

- ^ Gardiner, Bryan (2008-02-25). "Google's Submarine Cable Plans Get Official" (PDF). Wired. Archived from the original on 2012-04-28.

- ^ [1][] Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2010, February 5). Submarine telecommunications cables.

- ^ Clark, Bryan (15 June 2016). "Undersea cables and the future of submarine competition". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 72 (4): 234–237. doi:10.1080/00963402.2016.1195636.

- ^ Dunn, John (March 1987), "Talking the Light Fantastic", The Rotarian

- ^ Lindstrom, A. (1999, January 1). Taming the terrors of the deep. America's Network, 103(1), 5–16.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-08. Retrieved 2010-04-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) SEACOM (2010)

- ^ McCarthy, Diane (2009-07-27). "Cable makes big promises for African Internet". CNN. Archived from the original on 2009-11-25.

- ^ Conti, Juan Pablo (2009-12-05), "Frozen out of broadband", Engineering & Technology 4 (21): 34–36, doi:, ISSN 1750-9645, Archived from the original on 2012-03-16, https://web.archive.org/web/20120316161253/http://eandt.theiet.org/magazine/2009/21/frozen-out-of-broadband.cfm

- ^ Tanner, John C. (1 June 2001). "2,000 Meters Under the Sea". America's Network. bnet.com. Archived from the original onثمانية July 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Shapiro, S.; Murray, J.G.; Gleason, R.F.; Barnes, S.R.; Eales, B.A.; Woodward, P.R. (1987). "Threats to Submarine Cables" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-15. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ John Borland (February 5, 2008). "Analyzing the Internet Collapse: Multiple fiber cuts to undersea cables show the fragility of the Internet at its choke points". Technology Review.

- ^ The Embassy of the United States of America. (1959, March 24). U.S. note to Soviet Union on breaks in trans-Atlantic cables. The New York Times, 10.

- ^ Smith, Paul, Furse, Cynthia, Safavi, Mehdi, and Lo, Chet. "Feasibility of Spread Spectrum Sensors for Location of Arcs on Live Wires Spread Spectrum Sensors for Location of Arcs on Live Wires." IEEE Sensors Journal. December, 2005. Archived December 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "When the ocean floor quakes" Popular Mechanics, vol.53, no.4, pp.618–622, April 1930, ISSN 0032-4558, pg 621: various drawing and cutaways of cable repair ship equipment and operations

- ^ Clarke, A.C. (1959). Voice across the sea. New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.. p. 113

- ^ Jonathan Reed Winkler, Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008)

- ^ Carter, L.; Burnett, D.; Drew, S.; Marle, G.; Hagadorn, L.; Bartlett-McNeil D.; Irvine N. (December 2009). "Submarine cables and the oceans: connecting the world" (PDF). p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- ^ Martinage, R (2015). "Under the Sea, vulnerability of commons". Foreign Affairs: 117–126.

- ^ Emmott, Robin. "Brazil, Europe plan undersea cable to skirt U.S. spying". Reuters. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ Davenport, Tara (2005). "Submarine Cables, Cybersecurity and International Law: An Intersectional Analysis". Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology. 24 (1): 57–109.

- ^ Davenport, Tara (2015). "Submarine Cables, Cybersecurity and International Law: An Intersectional Analysis". The Catholic University Journal of Law and Technology: 83–84.

- ^ Paul, Nickles. Communications under the seas : the evolving cable network and its implications. MIT Press. pp. 209–226. ISBN .

- ^ Hecht, Jeff. Communications under the seas : the evolving cable network and its implications. MIT Press. p. 52. ISBN .

- ^ Fine, I. V.; Rabinovich, A. B.; Bornhold, B. D.; Thomson, R. E.; Kulikov, E. A. (2005). "The Grand Banks landslide-generated tsunami of November 18, 1929: preliminary analysis and numerical modeling" (PDF). Marine Geology. Elsevier. 215 (1–2): 45–47. doi:10.1016/j.margeo.2004.11.007. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 30, 2007.

- ^ "Top Story: Standby Net arrangements terminated in Pakistan". Pakistan Times. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "Communication breakdown in Pakistan – Breaking – Technology". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-06-29. Archived from the original on 2010-09-02. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "Pakistan cut off from the world". The Times of India. 2005-06-28. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "Learning from Earthquakes The ML 6.7 (MW 7.1) Taiwan Earthquake of December 26, 2006" (PDF). eeri.org. Earthquake Engineering Research Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

- ^ "Vietnam's submarine cable 'lost' and 'found' at LIRNEasia". Lirneasia.net. Archived from the original on 2010-04-07. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "Finger-thin undersea cables tie world together – Internet – NBC News". NBC News. 2008-01-31. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "AsiaMedia :: Bangladesh: Submarine cable snapped in Egypt". Asiamedia.ucla.edu. 2008-01-31. Archived from the original on 2010-09-01. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "SEA-ME-WE-4 Outage to Affect Internet and Telcom Traffic". propakistani.pk. Archived from the original on 2017-04-05. Retrieved 2017-04-04.

- ^ PT (2011-03-14). "In Japan, Many Undersea Cables Are Damaged". gigaom. Archived from the original on 2011-03-15. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ^ See TEAMS (cable system) article.

- ^ Kirk, Jeremy (27 March 2013). "Sabotage suspected in Egypt submarine cable cut". ComputerWorld. Archived from the original on 2013-09-25. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- ^ Grubb, Ben (2014-12-02). "Internet a bit slow today? Here's why" (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ^ "IMEWE submarine cable fault". Archived from the original on 2018-04-27.

- ^ "PTCL commissions Pakistan operations of AAE-1 submarine cable system".

- ^ Shapiro, S.; Murray, J.G.; Gleason, R.F.; Barnes, S.R.; Eales, B.A.; Woodward, P.R. (1987). "Threats to Submarine Cables" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-15. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ John Borland (February 5, 2008). "Analyzing the Internet Collapse: Multiple fiber cuts to undersea cables show the fragility of the Internet at its choke points". Technology Review.

- ^ The Embassy of the United States of America. (1959, March 24). U.S. note to Soviet Union on breaks in trans-Atlantic cables. The New York Times, 10.

- ^ Smith, Paul, Furse, Cynthia, Safavi, Mehdi, and Lo, Chet. "Feasibility of Spread Spectrum Sensors for Location of Arcs on Live Wires Spread Spectrum Sensors for Location of Arcs on Live Wires." IEEE Sensors Journal. December, 2005. Archived December 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "When the ocean floor quakes" Popular Mechanics, vol.53, no.4, pp.618–622, April 1930, ISSN 0032-4558, pg 621: various drawing and cutaways of cable repair ship equipment and operations

- ^ Clarke, A.C. (1959). Voice across the sea. New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.. p. 113

- ^ http://www.iscpc.org/information/Cableships_Page.htm سفن تمديد الكابلات حول العالم

- ^ http://www.nsw.com

- ^ http://www.offshore-technology.com/contractors/cables/teledenmark

- ^ http://www.marine.francetelecom.com/en/

- ^ http://www.globalmarinesystems.com

- ^ http://www.nttwem.co.jp/

- ^ http://www.sbsubmarinesystems.com/

- ^ http://www.emarine.ae/

- ^ http://www.ittelecom.com/

- ^ http://www.subsea7.com/

- ^ Gellman, Barton; Markon, Jerry (9 June 2013). ". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ Gellman, Barton; Blake, Aaron; Miller, Greg (9 June 2013). "Edward Snowden comes forward as source of NSA leaks". The Washington Post. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

-

^ "How The NSA Taps Undersea Fiber Optic Cables". http://siliconangle.com. 2013-07-19. Retrieved 2013-07-22. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ^ Diane Shalem (2019-07-02). "Urgent consultations in Washington, Moscow on reported US-Russian submarines in firefight". مسقط دبكة الإسرائيلي.

- ^ Diane Shalem (2019-07-03). "The mystery of the ultra-secret Russian "Losharik" submarine disaster". مسقط دبكة الإسرائيلي.

- ^ Alexandra Ma and Ryan Pickrell (2019-07-04). "The Russian submarine that caught fire and killed 14 may have been designed to cut undersea internet cables". businessinsider.

- Daily Wireless.org

-

Neil King Jr. (2001-5-23). "Deep Secrets: As Technology Evolves, Spy Agency Struggles To Preserve Its Hearing". وال ستريت جورنال. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

وصلات خارجية

- The International Cable Protection Committee -- includes a register of submarine cables worldwide (though not always updated as often as one might hope)

- Submarine Cable Market Overview, November, 2007 -- includes details of many major submarine cable systems

- Timeline of Submarine Communications Cables, 1850-2006

- History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy - Wire Rope and the Submarine Cable Industry

- France Telecom's Fishermen's/Submarine Cable Information

- Oregon Fisherman's Cable Committee

- Website with comprehensive list of cable landing sites and suppliers globally (contains many duplicates and incomplete data)

- 1939 Article on Laying Submarine Cables

- Mother Earth Mother Board - Wired article by Neal Stephenson about submarine cables

- Nature article - Geomagnetic induction on a transatlantic communications cable

- . Europhysics News (2004), Vol. 35 No 6.

الخرائط

- Alcatel Optical Fiber Submarine systems Map, 2005.

- Map and Satellite views of US landing sites for transatlantic cables

- Map and Satellite views of US landing sites for transpacific cables

- Kingfisher Information Service - source of free maps of cable routes in and around the UK/North Sea area

- New.com Undersea fibre cables - approximate inter-continental capacity of fibre cables, as of 2004